Deerlick Creek is located in the post-war Parkwoods-Donalda neighbourhood of North York. The stream runs roughly 3 kilometres from its northern point its mouth at the Don River, making it a tributary to the larger river and part of its watershed. Deerlick Creek passes through a couple of parks — Brookbanks Park and Lynedock Park — and crosses several streets. It is an interesting stroll through nature and suburbia, and through the layers of pre-contact, colonial, and post-war Toronto.

Source: Google Maps

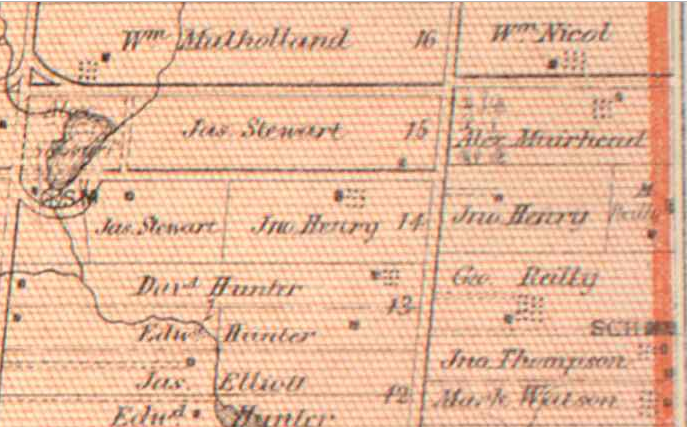

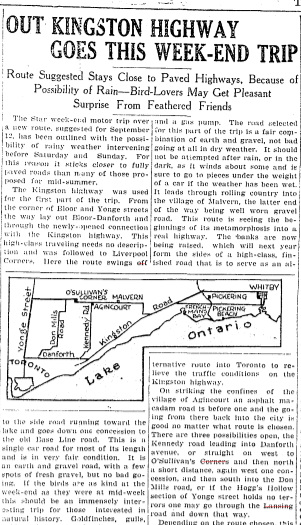

Deerlick Creek was given its name in the 19th century (as early as 1841) by farmers of the area, when deer and salmon could be found in the ravine. Unlike other colonial-era waterways in Toronto, there does not appear to have been mills or industry built on the stream, which suggests it was not a forceful current.

Source: Old Toronto Maps

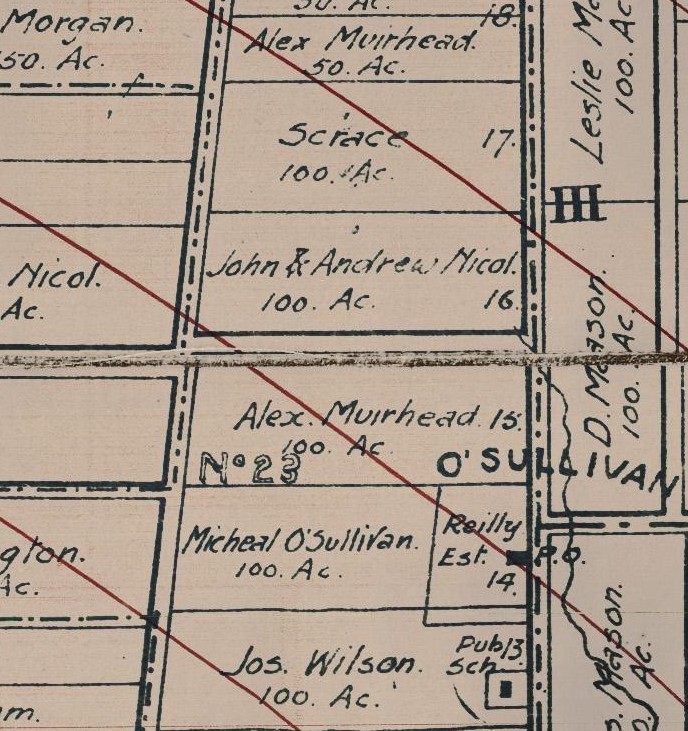

The current headwaters of the creek are in Lynedock Park, a locale which also has a middle school. The neighbourhood north of York Mills Road around the creek dates mostly from the early 1960s and is dotted with mostly post-war bungalows.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Curiously, these houses were not the first to be built here. In the 1950s, there were at least six houses built before the current neighborhood. Driveways curled up from York Mills Road, branching off to the houses. Deerlick Creek ran in the middle of them. In 1965, most of the houses were integrated in the neighbourhood. Beginning in the 1970s, more of the houses were razed for other homes and apartment buildings. Possibly two houses remain today — one house for certain and a potentially altered house. Both homes are identifiable through through their odd orientations compared to the street. Their garages face away from the street, pointing to the repositioning of their driveways, as well as a front door placed to the side in one.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Deerlick Creek was channelized and straightened beginning around 1960 when the neighbourhood was under construction. At its most northern point, the stream disappears into a culvert at Roywood Drive. A footbridge connects the park and schoolyard to the neighboorhood. There are improvements happening along the creek to combat area basement flooding.

Deerlick Creek ventures south under Lynedock Crescent. It is not clear how wide and powerful it might have been historically, but today, it is a narrow, shallow, and murky-looking waterway. Then, it disappears briefly under York Mills Drive.

On the other side, the ravine is part of Brookbanks Park. Deerlick Creek snakes around the park with paved and unpaved paths on either side of it and bridges crossing the creek. The stream is narrow here too and not fast flowing. Evidence of erosion is visible with some retaining walls. While a ‘wild’ element remains on a small level, sections have likely been straightened

Brookbanks Park is the physical heart of the Parkwoods-Donalda neighbourhood. It has multiple entry points and is a well used and valuable greenspace for the surrounding community. This interconnectedness is also present when one looks up from the ravine to see the backs of houses. The neighbourhood was built beginning in the 1960s. A by-product of the development was a lot of of the tree canopy in the ravine was lost. One would think its bio-diversity was also negatively impacted too.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Deerlick Creek passes under Brookbanks Drive. Like its similarly named park, the street also slinks through the neighbourhood. There is a great vista of the Brookbanks Ravine on the south side of the street which highlights its contours and the tree canopy.

Interestingly, this area has some tangible pre-contact history. Dr. Mima Kapches conducted digs in Deerlick Creek ravine in the 1980s and 1990s. The digs resulted in the discovery of a Meadowood cache blade from 1000 BCE and a small pebble containing a human face in effigy believed to be from 4700 BCE. Jason-Ramsey Brown writes that the discoveries have some archeologists believing the area of Deerlick Creek may have a season pottery production and firing campsite.

In the 1970s, the Toronto Field Naturalists surveyed Brookbanks Ravine and Deerlick Creek and noted 105 species of birds and 167 species of trees could be found in the valley. It also noted that while deer may have roamed freely a century ago, now the largest animal groups were squirrels and skunks. The Naturalists also noted the ravine was threatened by “tidying by the parks department and construction on the edge of the ravine by homeowners.”

Brookbanks Park ends at Cassandra Drive where a narrow path leads one to and from the park. Deerlick Creek veers southwest, under the highway, and flowing into the Don River at a golf course. An unpaved path seems to run next to its course, although it is unclear how far it stretches.

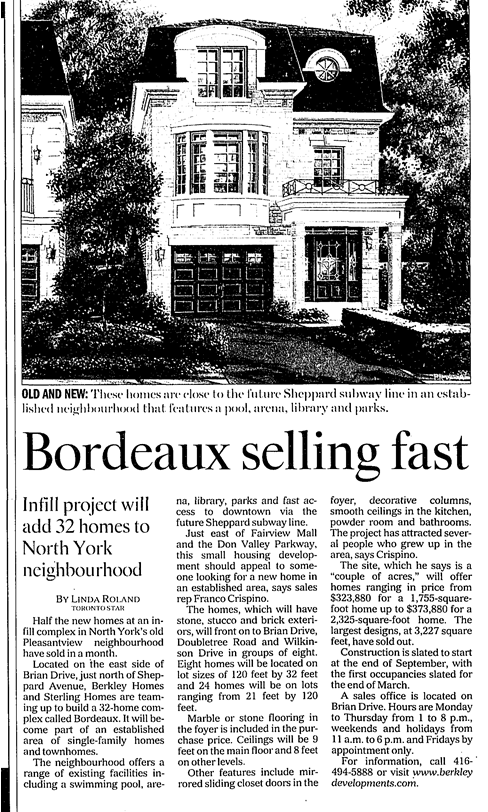

North from Brookbanks Drive, Valley Woods Drive is an interesting street sandwiched between the Don Valley Parkway and the ravine. Valley Woods itself was laid out beginning in 1965, much like the rest of the neighbourhood. At the foot of the street is Citadel Village, which at the time of its construction was a representation of idyllic, post-war, suburban living.

Citadel Village was designed by Tampold & Wells and was completed in 1967. It is a collection of townhouses surrounding a circular apartment — presumably the “citadel”. A 1966 promotional advertisement described Citadel Village as a “southern European village on a mountaintop with a thickly wooded ravine on the east and a panoramic view of the city to the west.” Other selling points in ads in the following years highlight the family-friendly development particularly in its spaciousness and lack of traffic, comfort, and proximity to local amenities and downtown (15 minutes by the new Don Valley Parkway!). Citadel Village is listed as Toronto heritage property.

Valley Woods Road slinks up the side of the ravine with connections to the park. It also has a bus serving the street. At the top of the street at York Mills Road, a new condominium and planned community are under construction, named “The Ravine”. The development will consist of several towers and homes, and replaces rental townhouses previously on the site. It is the next layer in the history of Deerlick Creek and its surrounding communities.

Works Consulted

“The Biggest Townhouses In Town.” The Toronto Daily Star, 9 Nov. 1968, p. 59.

“Brookbanks Park and Deerlick Creek.” Greck, https://www.greck.ca/Projects/Brookbanks-Park-and-Deerlick-Creek.

“Citadel Village.” The Toronto Daily Star, 22 Aug. 1966, p. 31.

Donvalleygirls. “The History of Brookbanks Park and Deerlick Creek.” Exploring Toronto’s Don Valley, Lake Ontario, and Green Spaces in between., 29 Feb. 2016, https://donvalleygirls.wordpress.com/2014/02/15/the-history-of-brookbanks-and-deerlick-park/.

“The Easy Life of Citadel Village.” The Toronto Daily Star, 20 July 1968, p. A50.

“Friendly People.” The Toronto Daily Star, 31 Dec. 1971, p. 40.

L, Mishy. Brookbanks Park and Deerlick Creek, https://mishylainescorneroftheworld.blogspot.com/2013/04/brookbanks-park-and-deerlick-creek.html.

Lakey, Jack. “Brookbanks Park Still Plagued by Damage from 2005 Flash Flood.” Thestar.com, Toronto Star, 1 Sept. 2014, https://www.thestar.com/yourtoronto/the_fixer/2014/09/01/brookbanks_park_still_plagued_by_damage_from_2005_flash_flood.html.

Little, Olivia. “Brookbanks Park in Toronto Comes with Plenty of Natural Beauty and a Rich History.” BlogTO, BlogTO, 14 Jan. 2021, https://www.blogto.com/city/2021/01/brookbanks-park-toronto-comes-plenty-natural-beauty-and-rich-history/.

“Metro Naturalists Set Plans to Preserve Area Ravines.” The Toronto Star, 26 Feb. 1975, p. C15.

“Parkwoods Donalda.” StrollTO, https://www.strollto.com/stroll/parkwoods-donalda/.

Quinter, David. “Toronto Butterfly Habitat Urged.” The Toronto Star, 6 July 1976, p. B1.

Ramsay-Brown, Jason. Toronto’s Ravines and Urban Forests: Their Natural Heritage and Local History. James Lorimer & Company Ltd., Publishers, 2020.

“The Warmest Townhouses in Town.” The Toronto Daily Star, 1 Feb. 1969, p. 25.

Yu, Sydnia. “Master-Planned Community in the Middle of Mother Nature.” The Globe and Mail, 2015 May 1AD, p. G2.