The following article originally appeared in the 2019 Volume 114 Annual Publication of the York Pioneer and Historical Society. It has been slightly edited and altered.

This work grew out of a 2016 walkabout article I wrote (to date, the most engaging piece I have produced) and a 2018 Jane’s Walk I led, both in efforts of telling the story of this historical Scarborough landmark. It was also inspired by several posts in the Scarborough, Looking Back… Facebook Group which highlights fond memories of The Tam and its fire.

If you have recollection of the old Tam O’Shanter Golf Club, please let me know or leave a comment below!

The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of The Tam!

By Bob Georgiou

The afternoon of October 3, 1971 was rough for the beloved Tam O’Shanter Golf, Curling, and Skating Club in Agincourt. On that day, the recreation centre of the Scarborough landmark burned to the ground.

The fire broke out around 4:30pm in the lounge of the curling complex after hockey mats inexplicably erupted in flames. The fire swept quickly through the building, feeding on the varnished woodwork. By 4:40pm, the complex was completely enveloped in flames.

Toronto Daily Star, Nov 4, 1971

Upwards of 10,000 people converged on the smoldering building, reported the Globe and Mail and Toronto Daily Star. Many of them arrived from afar, following the smoke trail. Ontario Police blocked off the area around Kennedy Road and Sheppard Avenue to allow emergency vehicles to reach the site. Firefighters battled the flames – but to no avail. Spectators watched from the parking lot of the recently -opened Agincourt Mall as the centre’s characteristic arches collapsed into the rubble.

The damage was devastating. The recreation complex was gone. Long-time Tam O’Shanter owner William G. Sparkhall vowed that day to rebuild the complex within a year, stating it would be better than the wooden construction that made it so vulnerable against the merciless embers. “I’ve spent a lifetime building this club up and I’m not going to stop now,” Sparkwell declared. “It cost me $1.5 million to build it and it will probably cost me $2.5 million to rebuild it.” The loss was otherwise estimated at $2 million.

Tam O’Shanter Fire, 1917. Credit: Toronto Public Library

There were fortunately no casualties on that hot October day. Staff had ushered to safety all two hundred children taking figure skating lessons. Still, the event called into question the future of the club’s hockey and curling operations, which hosted hockey league matches, a prominent hockey school, and one of the best curling facilities in Ontario and Canada.

The life of ‘the Tam’ began in 1933 when George Sparkhall, William’s father, purchased a 160-acre cattle farm on the south half of lot 29 concession 3, now the east side of Kennedy Road north of Sheppard Avenue. Using a barn as a clubhouse, Sparkhall turned the lot into a 104-acre pay-as-you-play golf course, calling it ‘Meadowbrook’, presumably referring to the meandering west branch of the Highland Creek situated in its southern end.

Globe & Mail, June 30, 1937

Globe & Mail, July 11, 1938

In the following years, the golf and country club served as social gathering point for the area, hosting banquets, weddings, dances, and other events such as the 1948 Easter party to kick off a $100,000 campaign for a new North Scarboro Memorial Centre.

In 1947, the Tam applied for a dining room and a lounge liquor serving license, under the recently enacted Liquor License Act, 1946. Under the provisions of the new law, residents could protest an application made within their district. A group of Agincourt residents did just that when 400 of them petitioned to oppose the Tam O’Shanter application, explaining that there had never been a need for the sale of beer in the village, the club house was used by teenagers for parties, and as the Tam was located on two major streets, the license would encourage drinking and driving. Owner William Sparkhall answered that the country club was actually outside the district’s borders and the application was only meant to sell beer to members.

Dance at Tam O’Shanter Boys Club, November 15, 1956. Credit: Toronto Archives

Over the years, the younger Sparkhall, who purchased the golf course from his father in 1938 and renamed it Tam O’Shanter, undertook several upgrades to the property, and added an adjacent lot bordering Birchmount Road. In 1954, the club improved several holes in its 18-hole course, and upgraded its clubhouse and dining room. Two summers later, members and visitors had access to the new and popular Emerald Pool.

Toronto Daily Star July 31, 1956

In 1958, a game-changing addition came in the form of a 12-sheet curling rink. The modernist structure was constructed of fieldstone and housed spectators’ galleries behind three four-sheet sections. It was the “largest in Canada devoted entirely to curling”. The Globe and Mail boasted that even before construction had completed, the club already had a “considerable response to a membership campaign” for new curlers. At this time, the main clubhouse added bowling alleys, two dance floors, two dining areas, and three lounges. Eight more curling sheets followed in 1961. The following year, the Tam could pride itself on “a rink six inches wider than that of Maple Leaf Gardens.” Together, the improvements made the Tam into a formidable and beloved social, sporting, and recreational venue.

Globe & Mail, Feb 26, 1958

While Sparkhall vowed golf would continue as usual after the fire (and indeed it reopened the next day and the following season), most of the club’s functions were severely compromised. A 3-day Oktoberfest scheduled to take place on the Tam grounds that weekend was shortened to a 1-day event at a different venue. Worse, however, the upcoming hockey season was greatly affected by the lack of a rink. The Wexford Hockey Association, whose teams played out of the Tam O’Shanter Arena, scrambled to find other facilities to host its games. North York Mayor Basil Hall elected to bring the matter to Metro Regional Council to see if it could offer assistance in relocating games.

Bruce and Margaret Hyland had to consider their next steps, too. The 5-time Olympic coaches — legendary figures in Canadian skating — ran a popular summer hockey school and the Canada Skating Club at the Tam. The hockey school was one of the largest in the world; Canadian hockey greats Frank and Peter Mahovlich, Kent Douglas, Paul Henderson, and Eddie Shack practiced at Tam O’Shanter Arena. The skating school was supposed to start a day after the fire. By December 1971 though, the Hylands announced initial plans for a $2 million arena built “on four acres of land between Victoria Park Avenue and Don Mills Road, just south of Finch Avenue.” It would be called the Hyland Ice Skating Centre.

1969 Toronto City Directory of Kennedy Road. Credit: Toronto Public Library.

The club’s 300 curling members elected to remain together, and used membership dues to lease space offered by other clubs in the Toronto area. In June 1972, officials at the Tam-Heather curling club announced they were ready to resume their activities in October of that year. They hoped a new sports complex would be ready by the first anniversary of the fire at Tam O’Shanter.

Interestingly, despite William Sparkhall’s declaration to have the recreation centre up and running in 1972, he – under the Tam-Land Estates Ltd. banner – applied shortly after the fire to rezone the 118-acre golf course to accommodate residential and commercial enterprises. The golf course at the time was zoned for agriculture in its western half and recreation in its eastern half. Tam-Land Estates planned to build a housing and high-rise development on the property. Community opposition, led by future Scarborough Controller and Mayor Joyce Trimmer, successfully fought to keep the area as open public space, harnessing the power of Trimmer’s adamant and ultimately effective letter writing campaign.

These debates around the future of the Tam O’Shanter site also coincided with Metro Parks Commissioner Thomas Thompson’s desire to acquire more parkland for Metro Toronto. The events following Hurricane Hazel in 1954 led the Metro Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA) to acquire flood valleys that would push Metro’s parkland to nearly 7,000 acres. However, outside of ravine lands, the region was in short supply of recreation lands to service its expected growth. A potential solution was the acquisition and transformation of private golf courses as they became available.

In what the Globe And Mail called “a bold step toward parks’, Metro Parks Committee allotted $5 million dollars in Metro Council’s 1972 budget to acquire the 165-acre York Downs Golf Course in the Bathurst Street and Sheppard Avenue area and the 118-acre Tam O’Shanter Golf Club in Scarborough. The amount was more than double what Metro spent on parkland acquisition in the previous 10 years. A special subcommittee consisting of Metro Chair Albert Campbell, North York Mayor Basil Hall, Scarborough Mayor Robert White, Metro Parks Commissioner T.W. Thompson, and Metro Planning Commissioner Wojctech Wronski also pushed back Sparkhall’s redevelopment proposal indefinitely so that it could study and report on the possibility of acquiring Tam O’Shanter and York Downs.

With news of the Tam’s availability as potential park space, decision-makers and media urged the purchase. As one Toronto Star editorial put it, Metro Council had to “grab the chance for green space”. It argued that Tam O’Shanter was parkland “in a crowded area” and “there was no obvious recreational land coming on the market nearby.” New Metro Chairman Paul Godfrey called the chance “a golden opportunity that won’t come again”. Another positive was it would not require the demolition of any homes, which was notable because Thomas Thompson’s Metro Parks Committee was also recommending the demolition of 254 houses on the Toronto Islands to create more parkland.

With the sub-committee’s final decision to ultimately buy the course, questions in 1973 revolved around who would pay, how they would pay, and how much they would pay. Metro had $3.5 million budgeted for parks for the next five years; if it took a gander on Tam, it could affect its ability to acquire other parks. Scarborough Controller Karl Mallette added that Scarborough taxpayers could “easily afford” a raise on taxes to pay for new parkland and facilities, such as the new park at Tam O’Shanter. In February of that year, Campbell announced a proposal of a three-way agreement which would see the Ontario government cover half the course’s costs and Metro and Scarborough covering a quarter each. The same formula was used to purchase the York Downs Course. An unknown factor was Tam-Land Estates’ asking price, which was reportedly between $12,000 to $100,000 an acre. In September 1973, the price was eventually set at $10.8 million, a number that had East York Mayor Willis Blair suspecting was too rich. However, two different appraisals valued the land at $10.6 million and $11 million.

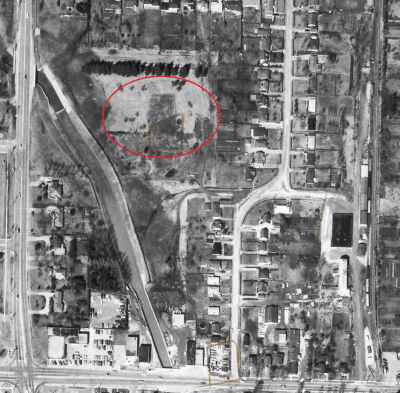

Aerial view of the Tam O’Shanter Golf Course, 1975. Bridges that formerly crossed the West Highland Creek were removed, possibly as the course was awaiting reorganization.

Meanwhile, the Tam’s curling club and hockey and skating schools happily found new homes. Boasting a membership of 540 and set to reach capacity of 640 by the start of the following season, the Tam-Heather Curling Club opened its new eight-sheet, $500,000 complex in March 1973 at Morningside Avenue and Highway 401. Also in 1973, Bruce and Margaret Hyland successfully opened Metropolitan Ice Skating School (later Centre Ice) on Victoria Park Avenue. The complex had three ice surfaces, one of which Mr. Hyland operated a hockey school.

Finally, two years after the fire that devastated the Tam, officials met in Metro Chairman Paul Godfrey’s office to formalize the purchase of Tam O’Shanter Golf Club. On November 10, 1973, William Sparkhall, president of Tam Land Estates, accepted two cheques totalling $10,825,000 for the 118-acre golf course from Godfrey, Education Minister Thomas Wells, Scarborough Mayor Paul Cosgrove, and Fred Wade, chairman of the MTRCA. Tam-Land Estates retained some land for its own redevelopment purposes. With the purchase of Tam and York Downs, Metro Parks also recommended the creation of an inventory of other private courses with the goal of purchasing them in the future. The MTRCA would officially own Tam O’Shanter, but Metro Parks would oversee it.

Following the acquisition, several outlying details remained about the function and form of the new Tam O’Shanter. Scarborough Council disagreed with Metro about the property’s apparent decided future as a municipal golf course. The borough understood that the option was open for it to become a park, and even though discussions during negotiations mentioned that Tam O’Shanter could either continue as a golf course or become a park or a mixture of the two, there was no formal resolution. Wells, the Progressive Conservative representative of Scarborough North, the provincial riding housing Tam O’Shanter, asserted in a February 1973 edition of the Globe and Mail, “It is essential that this site be retained as open space but not necessarily as an 18-hole golf course.” Despite the disagreement, new Metro Committee Parks Commissioner Robert Bundy said the site was “well located for a golf course” and Tam O’Shanter remained a public course – possibly because it was one of the only courses in the east end of Metro Toronto.

The golf course required major upgrades, however. While minor improvements kept the golf club operational through the 1970s, the quality of the greens, which required a new irrigation system, was so poor that Metro Parks lowered its fees in 1975 by 50 cents. With the damage to and the eventual demolition of the old Tam complex in the years after the purchase, the course also required a new clubhouse. In the first half of the 1980s, Tam O’Shanter underwent $800,000 worth of upgrades to update and reconfigure its course with a new entrance of Birchmount Road. Its new clubhouse opened on May 7, 1982.

Aerial, 1983. Credit: City of Toronto Archives

In 1985, Sparkhall and Co. – seemingly the new banner of Tam-Lands Estates Limited – looked to redevelop the land south of the course and north of Agincourt Mall. It proposed, and was allowed to build “1000 apartments, 23,225 square metres (250,000 square feet) of offices, up to 6,040 metres (65,000 square feet) of commercial use, libraries, day nursey, and educational facilities on 6.16 hectares (15.23 acres) of land on Kennedy north of Bonis [Avenue].”

Just as there had been opposition in 1971, residents of Bonis Avenue mobilized to fight the proposal. The community assembled a petition of 500 names and packed the Scarborough Council chambers in March 1985 to voice disapproval of their neighbourhood becoming “a mini-downtown.” Along with the scale of the development, another sticking point was the proposed extension of Bonis, which was at the time a dead-end street running east from Birchmount Road, stopping at the old lot border. The plan called for its lengthening to connect with Cardwell Avenue at Kennedy Road. Residents, including Controller Joyce Trimmer (who beat out former Controller Karl Malette in the 1974 election), argued that the street would only serve as a high-speed detour for Sheppard Avenue traffic. After more consultations, the project did not go through.

Plans for development along Bonis Avenue surfaced again in 1988, this time spearheaded by Tridel Corporation. The new proposal involved “four 24-storey condo towers with a total of 1,112 units, a five-story building with 7,961 square metres of office space, a one-story building with 5,580 square metres of retail space, and two-storey, 1953-square metre public library.” The inclusion of a library was notable because a 1977 plan suggested the erection of a much-needed district library on a portion of the Tam O’Shanter property turned over to Scarborough for municipal parkland. This was opposed by Trimmer and was ultimately nixed by Metro planners.

Despite being a slightly more scaled back version of the Sparkhall and Co. project, Tridel Corp. faced similar challenges and objections as its predecessor. As was the case three years ago, the property, zoned for institutional and recreational use, would have to be rezoned. Planning and traffic studies again recommended an extension of Bonis Avenue. Opponents said the development had double the amount of allowed units. The Highland Heights Community Association warned the street would become a ‘traffic nightmare’, which would bring in 1,000 cars in the evening rush hour (Tridel contended 335 cars). Even with the opposition, calls for the developer to scrap the project largely went unheard.

In October 1988, despite last minute objections, Scarborough council approved the $500-million dollar project behind Agincourt Mall. It was the second major condo project approved in the span of a month in the borough. On September 6, Council approved $1.5 billion, 2,420-unit development – also by Tridel – at the Scarborough Civic Centre.

As a part of the Agincourt deal, Scarborough also received a 1,200-square-metre parcel of land worth more than $300,000 for a $4.5 million library. Tridel also gifted $500,000 for its construction as well as $1.6 million for day care, park development and landscaping. The new Agincourt Library branch opened in 1991 on Bonis, moving from Agincourt Mall and continuing a legacy dating back to 1918.

Also in 1991, ‘The Greens at Tam O’Shanter’, the first tower in the phased project, opened. Described by a 1989 Toronto Star ad as “a magnificent collection of country club style residences overlooking the manicured greens and fairways of the renowned Tam O’Shanter Golf course in Scarborough”, it is a 24-storey construction with “211 one, two and three bedroom suites – many of which open up onto private terraces” which “range from 787 square feet to 1,782 square feet. Its marketing harnessed “the royal and ancient” tradition of golf as it was played on old Scottish courses like St. Andrews and Leith Links, when the game “was the sport of kings”. Although it did not do so in the end, the advertisement could have also referenced the 50+ year history of golf at Tam O’Shanter.

Toronto Star, Oct 7, 1989

The next parts of the Tridel complex – 28 brownstone townhouses and 3 more 24-storey condos – would open over the next twenty years. One of the condos – 1998’s “The Highlands at Tam O’Shanter” at 228 Bonis Avenue – roughly occupies the former site of the Tam’s famed clubhouse and recreation centre.

Today, the Tam O’Shanter Golf Clube operates an 18-hole, Par 72 course from mid-April to mid-November.