On September 14, 1878, The Globe reported on “The Great Rainstorm”, a phenomenon that overwhelmed Toronto and the Don River. A view from the Necropolis Bridge, the crossing near the cemetery, described the water swelling gradually in the morning, but overflowing by eight o’clock. By mid-day the bridge had been completely swept away. The river was a wild scene of flowing water and debris. Fortunately, the newspaper reported a week later that the bridge was re-erected and travel was resumed. The dramatic event is one episode in the life of the bridge and road, which would come to be a notable, lost part of Toronto’s history and geography.

The Winchester Street Bridge

The crossing at Winchester Street and the Don River was an important one in and out of the City of Toronto. And potentially one of the oldest. A bridge has existed in some form since the days of John Graves and Elizabeth Simcoe. That latter wrote in her journal of “Playter’s Bridge,” a crossing made of a fallen butternut tree. Later versions of the bridge included sturdier constructions, albeit were prone to washouts as per the 1878 storm and another storm in 1894, which resulted in its “almost complete destruction.” They were also variously named: The Necropolis bridge as mentioned, the Winchester Street bridge which was the most common name, and simply the Don Bridge (albeit this was more famous as the crossing at today’s Queen Street).

Source: York University Archives

Source: Old Toronto Maps

In a pre-Bloor Viaduct Toronto, the Winchester Street Bridge and the road extending from it was the most northern path to and from the city on the east side. Its origins lay in the 1840s, likely as an alternative to the Queen Street bridge for travelers heading into market. Its location at this junction points to its prominence as a stop on the way into and out of town — and an ideal spot for a tavern. The Don Vale House stood on the west side of the Don River near the bridge from the late 1840s. It was noted as a popular yet rowdy locale, particularly for gambling activities. It was torn down in 1876. There was also an old toll-gate house which “stood for so many years at the foot of the hill close to Winchester Bridge,” which was removed in 1882. It was reported as an “eyesore” and “tramps who have lodged there free of cost will miss the old shanty.”

Source: Old Toronto Maps

Source: York University Archives

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Over its history, numerous repairs have been made to the Winchester Street bridge, including rebuilding it altogether. In addition to a new causeway built after the 1878 storm, it was reported in October 1885 that the “new Winchester-Street bridge” was almost ready; it was already planked, and the approaches were just about complete. In late 1888, the idea of erecting a high-level bridge was being explored. In 1894, the bridge was described as “long been regarded as unsuitable and unsafe during floods,” as proven by the storm that decimated the bridge that year. In 1902, a proposal was endorsed to fit the bridge with $10,000 of lumber to repair the bridge. In March 1909, the bridge was condemned and majorly repaired and rebuilt at a cost of $15,000. It was reported that during this time, travelers on the Danforth would have to use the Gerrard Street bridge as an alternative until the bridge opened several months later. This somewhat regular need to repair or rebuild the bridge might reflect its frequency of use and its proneness to disaster caused by the Don River.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Source: City of Toronto Archives.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Source: City of Toronto Archives.

Source: Toronto Public Library

Here The Road Winds…

The winding road on the east side of the bridge was curiously not also named Winchester Street. Rather, it took on several monikers throughout its history. It must be noted that it is not easy to track the changes as its naming in maps and directories does not appear to be consistent — that is, sometimes it is not named at all or concurrent sources will name it differently. The first names identified in the 1800s seem to have been the similarly related Don Road, Don and Danforth Road, and Don Mills Road. After the turn of the century, it took on Winchester Drive (or Road), which is likely its most famous name. Its final evolution was as Royal Drive.

Source: Toronto Public Library

Source: Goads Toronto

It must also be noted that Winchester Drive was related in name and geography to the modern Broadview Avenue, but that connection and timeline is somewhat murky. An old aboriginal route lent itself to a new road in 1799, running east from the Don Bridge at Queen Street northwards to the saw and grist mills on the Don at about Pottery Road. It would aptly be named “The Mill Road”. In an 1884 annexation, The Mill Road was split in name north and south of Danforth Avenue into Don Mills Road and Broadview Avenue, respectively, possibly reflecting the odd, angular path taken by modern Broadview as it crosses Danforth Avenue.

However, in somewhat conflicting evidence, the 1856 Directory splits the two roads into The Mill Road, from Queen Street to Danforth Avenue, and The Don (and Danforth) Road, from Winchester Street to north of Danforth into Todmorden. This meant that for a time, the road leading northeast from the Winchester Street bridge and the road northeast of The Danforth was the same continuous road, even if their origins may not reflect that. Both roads were named Don Mills for a time as well.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

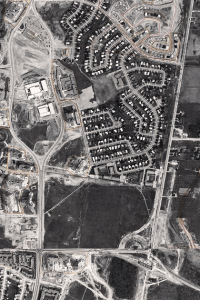

Winchester Drive would run along the river before turning east to pass under the Canadian Pacific Railway subway (appropriated also called the Winchester Street subway). In 1918, a flood caused by an ice-filled Don River made the road impassable, pointing to the low-lying situation of the southern part of the street. As it curled northeastward, it was positioned between two ridges, with Broadview Avenue overlooking on the east side. This followed the topography of the former Dallimore Creek, a tiny Don River tributary. At the top of the hill was the Taylor Tollgate, which was situated on the south side of Danforth Avenue in the corner between Winchester and Broadview Avenue.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Source: City of Toronto Archives.

Source: City of Toronto Hospital.

Source: City of Toronto Archive

Source: City of Toronto Archives

In 1901, the Swiss Cottage Hospital for smallpox was built on the west side of Winchester Drive. The isolation hospital was formerly located near the Don Jail and moved to a more remote area north of Riverdale Park when life around Gerrard Street grew busier. Winchester Drive had very few dwellings on it — if any at all. The Globe reported on its opening:

Constructed for its estimated cost, $5000, it is a picturesque structure of brick and stone, in the Swiss style of architecture. Bosomed in the precipitous cliffs that overlook the eastern banks of the Don, it is ideally situated. Looked at from the river flats it occupies a commanding height, yet behind and beside it to a height of 40 feet above it rise the steep banks of the Don. Taylor’s road winds up the cliffs just south of the hospital, but separated from it by a deep ravine. The hospital is practically in the centre of 150 acres of natural park land, and far from habitations.

The Globe, November 27, 1901

In 1927, it was reported that the hospital would close as it was deemed inadequate to deal with recent smallpox epidemics. The Swiss Cottage stood until 1930 after facing its unfortunate end by fire.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

The Royal Drive

Winchester Drive took on its final life in 1939. It was renamed Royal Drive to coincide with a visit by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Their motorcade traveled down the road into Riverdale Park for a demonstration by schoolchildren. Royal Drive would be used again in a similar manner in a subsequent royal tour in 1951 by Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh. It was reported at the time that the street would need to be completely resurfaced as it was covered in potholes. Princess Margaret traveled down the street in 1958, the last time a British Royal would do so.

Source: Toronto Star Archives

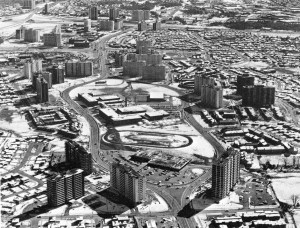

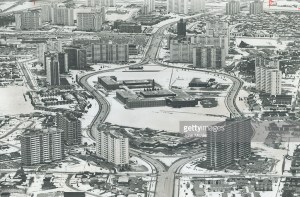

Royal Drive met its end via the Don Valley Parkway project in the late 1950s. On the west bank of the river, the road descending down from The Necropolis was removed near the river to make way for the Bayview Extension. Today, Winchester Street ends at the top of the hill near Riverdale Farm and the cemetery. The Bayview Extension also necessitated the removal of the now-orphaned Winchester Street Bridge.

Source: Globe and Mail Archives

Source: Globe and Mail Archives

On the east bank of the river, the roadbed for Royal Drive was also removed and replaced at its north terminus by an onramp to the northbound Don Valley Parkway. Eastbound travelers on the Bloor Viaduct might note that a sign for Royal Drive hangs over the entrance to the ramp. According to the City of Toronto, this marker does name the highway entrance as Royal Drive. Interestingly, however, Royal Drive does not appear on the city’s Road Classification List as a street.

Source: Google Maps

To compound the issue, a trail running on the table of land adjacent to it and the former Danforth Lavatory and City Adult Learning Centre is marked on Google Maps as Royal Drive. This path continues down into the valley, crossing over the onramp via a bridge and continuing into Riverdale Park.

Whichever is the case of the “real” Royal Drive, the lack of complete erasure of the name is likely intended to honour the royal tours of the past decades. It also aids in keeping alive the history of an early and prominent Toronto street.

Sources Consulted

Attachment No. 4 Historical Chronology – City of Toronto, http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2015/pb/bgrd/backgroundfile-85136.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar. 2024.

“Avenue Road Extension.” The Globe, 27 Sept. 1902, p. 22.

Axon, Elizabeth. “Some Memories of Old Don Mills Road.” The Globe and Mail, 4 June 1955, p. 19.

Bonnell, Jennifer. Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley. University of Toronto Press, 2014.

“Bridge Condemned.” The Globe, 18 Mar. 1909, p. 4.

Cabbagetown Uncovered: The Story of Toronto Can Be Found by Following …, http://www.toronto.com/news-story/6442876-cabbagetown-uncovered-the-story-of-toronto-can-be-found-by-following-the-don-river-and-its-history/. Accessed 24 Mar. 2024.

“City Council Yesterday.” The Globe and Mail, 3 Oct. 1939, p. 5.

“City News.” The Globe, 2 Feb. 1882, p. 10.

“City News.” The Globe, 21 Sept. 1878, p. 8.

City of Toronto. “An Infectious Idea: Hospitals and Ambulance Services.” City of Toronto, 24 Nov. 2017, http://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/online-exhibits/web-exhibits/web-exhibits-local-government/an-infectious-idea-125-years-of-public-health-in-toronto/an-infectious-idea-hospitals-and-ambulance-services/.

“City to Spend $40,000 Primping for Royal Visit.” The Globe and Mail, 12 Sept. 1951, p. 4.

Davetill. “1951 Royal Visit.” Toronto Old News, 13 Oct. 2020, torontooldnews.wordpress.com/2020/10/12/1951-royal-visit/.

“Debris Strewn in Don Valley.” The Globe, 27 Feb. 1918, p. 11.

“Don Vale House.” Don River Valley Historical Mapping Project, maps.library.utoronto.ca/dvhmp/don-vale-house.html. Accessed 23 Mar. 2024.

“The Earth Trembled.” The Globe, 1 Apr. 1896, p. 12.

“Gerrard Street Bridge.” The Globe, 15 Nov. 1878, p. 2.

“The Great Rainstorm.” The Globe, 14 Sept. 1878, p. 8.

Lambert, FW. “‘Don Mills’ Disappears.” The Globe, 3 Sept. 1938, p. 6.

Limeback, Rudy. Rediscovering Royal Drive, rudy.ca/rediscovering-royal-drive.html. Accessed 23 Mar. 2024.

“Municipal Items.” The Globe, 24 Dec. 1888, p. 3.

“Must Raise The Money.” The Globe, 13 May 1909, p. 7.

“New Smallpox Hospital.” The Globe, 27 Nov. 1901, p. 9.

“Notes.” The Globe, 5 Apr. 1894, p. 5.

“Old Swiss Cottage May Be Closed Soon.” The Globe, 16 Dec. 1927, p. 14.

“Public Notice.” The Globe and Mail, 10 July 1958, p. 10.

The Ravines Reach of the Don River, http://www.lostrivers.ca/content/Ravinesreach.html. Accessed 23 Mar. 2024.

Robertson, John Ross. “Don Vale House, c. 1870.” YorkSpace, Landmarks of Canada, 1 Jan. 1870, yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/items/f56c0b9e-17c5-406d-a89d-c64eb9cd7b23.

“Royal Drive.” The Globe and Mail, 8 May 1959, p. 13.

“Royal Procession.” The Toronto Daily Star, 11 Mar. 1939, p. 1.

SCADDING, HENRY. Toronto of Old. OUTLOOK VERLAG, 2020.

“A Tavern Stand to Be Let or Sold.” The Globe, 6 Apr. 1858, p. 3.

The Tollkeepers Cottage and Early Roads, http://www.lostrivers.ca/content/points/earlyrds.html#dmr. Accessed 23 Mar. 2024.

“Winchester Street Bridge.” The Globe, 24 Nov. 1885, p. 10.