Note: This is the second article in a series which aims to describe the 230-year evolution of the Castle Frank area. The first part is available here.

“The Sugar Loaf hill stands alone in the Don Valley. It is still covered with woods that join with those of Castle Frank, a quarter of a mile off in the woods, between the two hills, is a pine-tree in whose top is a deserted hawk’s nest. Every Toronto school-boy knows the nest, and, excepting that I had once shot a black squirrel on its edge, no one had ever seen a sign of life about it. There it was year after year, ragged and old, and falling to pieces. Yet, strange to tell, in all that time it never did drop to pieces, like other old nests.”

E.T. Seton, Wild Animals I Have Known

In 1898, author, naturalist, and artist Ernest Thompson Seton released his famous Wild Animals I Have Known, a compilation of short stories from his time exploring Toronto’s wilderness in the 1880s and 90s. In particular, Seton spent a lot of time in the Don Valley and Castle Frank Hill. English-born Seton grew up in nearby Cabbagetown.

E.T. Seton’s tales recounted the stories of the certain wildlife inhabiting the district, including Silverspot the Crow, Red Redruff the Patridge. He also noted other animals such as the blue jay and rabbit. Prevalent in Seton’s characterization of the fauna of the area were the old pines, hemlocks, grapes, and berries, altogether painting a pristine picture of the hill.

Decades later, another Don Valley explorer, conservationist Charles Sauriol also recounted the hill:

“The visitor who glanced down from the ramp of the viaduct, sees the top of the hill almost level with the floor of the bridge. The C.N.R. line flanks the hill on the east. North-westwards, a panorama of woodland (Old Drumsnab), becomes in summer a vista of undulating waves of billowy leafage extending towards Rosedale Ravine.”

Charles Sauril, Tales of the Don

Sauriol spent his summers between the 1920s and the 1960s in a cottage in the Don Valley. He was an advocate for the preservation of the valley.

The Castle Frank that Seton knew and explored was during a period in which the hill was largely untouched since the activities of the Simcoes and others, but would be on the cusp of major changes. The last two decades of the 1800s saw a transformation of and debate over the future of the hill and valley(s) below. As history moved into the following century, it would see an intensification in housing, three major public works projects, and an institutional additional – all that would change the complexion of the hill snd its surrounding area forever.

A New…and Newer Castle Frank

Walter McKenzie was the Clerk of the County Clerk for Toronto. He was also a former soldier. By the 1850s, he had taken up residence on Castle Frank Ridge. Along with a house, which he also called “Castle Frank,” there was an orchard and vineyard overlooking the Don River, located north of the spot where Mr. Simcoe built his cottage. It was the first permanent home on the hill since the ancient Castle Frank burned down in 1829.

In 1857, McKenzie placed an advertisement in The Globe selling “About Four Hundred Standing Pines,” located on the forested hill. McKenzie was a well-connected man in Toronto, particularly in the law profession; his son-in-law John Hoskins, also a lawyer, lived in the nearby “Dale” estate. Drumsnab, the other neighbour 19th century prominent estate, was also occupied by lawyers, first William Cayley and then Mr. Maunsell B. Jackson. McKenzie passed away in 1890.

Source: Globe and Mail Archives

Albert Edward Kemp was a very successful businessman who founded the Kemp Manufacturing Co., metal located at Gerrard Street East and River Street. In 1900, he entered federal politics, rising to prominence as Minister of Militia, a role that led to his knighting. In 1902, as a member of Toronto High Society, he built “New Castle Frank” on the site of McKenzie’s Castle Frank. Kemp died in 1929; his mansion stood until the 1960s.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Castle Frank Brook & Rosedale Valley Road

“Immediately under the site of Castle Frank, to the west, was a deep ravine containing a perennial stream known and marked on plans as ‘Castle Frank’ Brook, which entered the Don at one of the ‘Hog’s Backs’ referred to, where also was a small island form in the river…”

Henry Scadding, 1895

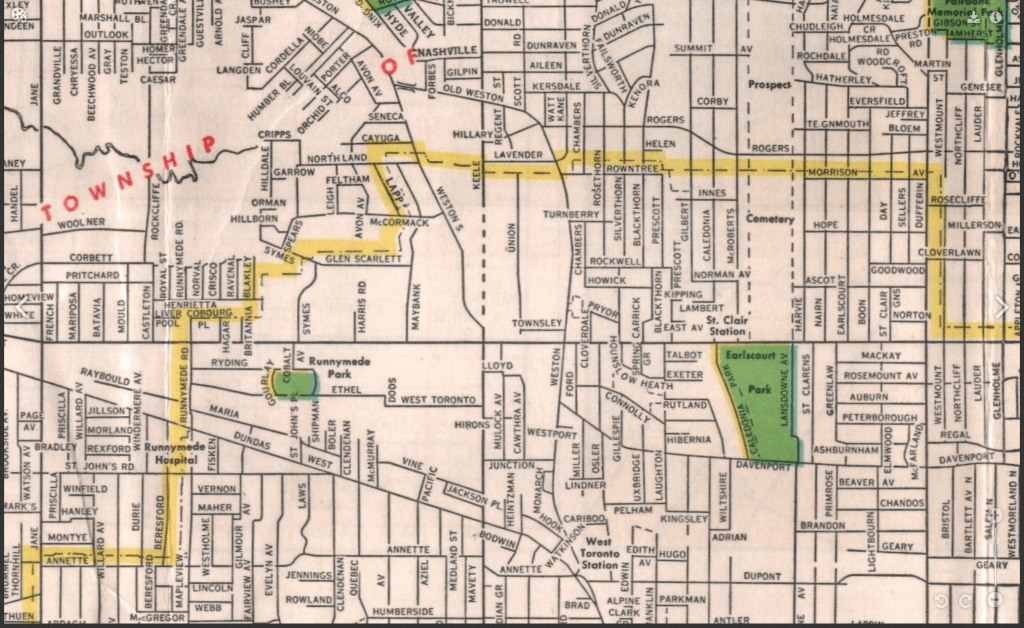

The Don River tributary known as Castle Frank Brook ran in a northwesterly direction to its heads near Dufferin and Lawrence. It is also known by other names: Severn Creek and Brewery Creek after the Severn Brewery, formerly located where the stream crossed Yonge Street. It also has gone by Davenport Creek, possibly because it passed through the Davenport estate.

Plans for a road and sewer through Castle Frank Brook ravine began in the late 1880s. The reasons for its transformation were twofold. First, following a general public health phenomenon in the city which called for the burial of polluted open waterways and creeks, it was decided to put Castle Frank Brook into a culvert. The creek’s state had deteriorated as the “northern district” had developed. Second, the idea of the road gained traction following a general movement towards “park drives” or “parkways.” The eventual Rosedale Valley Road married the two goals.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

The Globe reported:

The plan for the Davenport Creek ravine drive provides that it shall leave the road near the Winchester street bridge, on the way to the Silver Creek drive, and descending in the ravine follow near the line of the present creek. After passing St. James Cemetery, the drive will go through the property of Mr. Walter Mackenzie. After crossing the Castle Frank road it passes through the property of John Hoskin, S James, Margaret James, H J Clark, J L Thompson, R K Burgess, Alfred Chapman, William Croft, George and James Murray and F E Hodgson.”

The Globe, March 5, 1887

In 1887, Toronto City Council approved the expropriation of “a sixty-six foot roadway through it [Rosedale Valley] on the local improvement principle and the laid the sewer in the new street.” St. James Cemetery agreed to give the city any lands without any cost to the city. In the 1890s, the area was graded and the necessary construction took place. Awards were made to property owners by the city.

But the road construction was not without controversy. The City expropriated parts of the estates listed above — or so it thought. A clerical error did not properly register the expropriation, making it and the opening of the street illegal. The by-law outlining the expropriation was sent to the Registry Office to be registered in 1888. However, it should have been accompanied by a plan by Unwin Sankey and Browne, showing the land to be expropriated so that the affected properties could be identified. The plan was not sent, and the expropriations were not registered. The error was not discovered until a decade later. Rosedale Valley Road was opened without officially expropriated the needed lands.

The affected owners protested about their requirement to pay their share to open the road. The idea seems to be that Rosedale Valley Road was to be opened as a ‘local improvement project’, meaning that affected residents of the area were supposed to fit the bill to build the road. With this error, the courts quashed residents of any obligations – effectively placing the City of Toronto and its general tax base on the hook. In early 1899, the city registered a new bylaw regarding Rosedale Valley Road, and the lawsuits continued regarding the “debentures” of the street. It is unclear how the matter was resolved.

In 1897, the road was described as “…one of the coolest, shadiest and most beautifully picturesque roads in or near this city.” It is a description that holds today.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

In 1905, it was briefly proposed by Alderman McBride to make Rosedale Valley Road into a ‘speedway’ for horses from Park Road to Winchester Street. St. James Cemetery stated they would have never donated the land for the road if this would be the plan.

The Cemetery & The Park

St. James Cemetery opened in 1844 across the ravine opposite Castle Frank on donated land from the Scadding estate (previously the Simcoe estate). By 1897, a proposal existed to expand the cemetery’s grounds north of Rosedale Valley on Castle Frank Hill. The plan proved to be very controversial.

The proposal at heart looked to convert the land on Castle Frank Ridge into parkland and space for graves. The problem was the hill was subdivided with lots and owners by at least the start of the decade.

Source: City of Toronto

In 1897, Mayor Fleming and a contingent of politicians and ‘leading citizens’ toured Toronto by motorcar as they assessed potential park sites. They began at Queen Street and Logan Avenue. Reaching and crossing the Don, they scouted Sugar-Loaf Hill, a thickly wooded triangular hill that was said would make a picnicking area as part of the ‘Parks Plan.’ Next, they noted “the steep and wooded eastern side of Castle Frank, for the securing of which the Mayor is negotiating with owners of the St. James’ Cemetery, who have bought that whole district from Dr. Hoskin.” This latter point is important as it signaled a disputed future for Castle Frank Hill.

A NATURAL PARK

As one drives up the Ravine road on the right hand, as far east as the Don, all this territory, undesecrated by the end of man, with its three and a half acres of indescribably lovely side-hills and twenty-three acres acres of additional property on the summit, is to be virtually owned as a public park by the city of Toronto on certain conditions.

The three and a half acres is to be a gift to the city from Dr. Hoskin. The owners of the St. James’ Cemetery will control the flat at the top and provide for its beautification and maintenance. They ask that the city allow them to use the level land on the Castle Frank eminence as a burial ground, and that the city build a road from the drive to the top of the hill, so that a hearse can safely ascend the incline. This road will cost about $2,000 and a fence to enclose the whole cemetery park another $1,000. This is really the sole cost to the city for this magnificent park.

The Evening Star, July 17, 1897

In September 1897, the owners of lots 28 to 31 Castle Frank Avenue made a protest to the city about the cemetery extension, which they argued would destroy their property as it would be located adjacent against a cemetery.

Then, a Mrs. Mary Hebden, owning 10-13 Castle Frank Avenue of plan 686, filed a formal suit:

“…to restrain the city and the churchwardens of St. James’ from passing any by-law or resolution to permit burial on any of these lots, or to allow the churchwardens to enlarge the cemetery, or to perform any interments within the city limits, outside the limits of the present cemetery.

It also sought to prevent the city from amending any standing by-law as to burials within the city limits.”

The Evening Star, October 19, 1897

Mrs. Hedben’s suit against the city was heard several months later. Her lawyer, Mr. Hodgins, asked for an order to prevent the cemetery from adding more lands and for any agreement to exist between the cemetery and the city. This was denied as City Council could vote how it wanted. Hodgins then argued a statute that prevented cemeteries from being established within city limits but the law did not apply either.

In October 1897, the cemetery was anxious to have the by-law passed. Its trustees met with the City Board of Control to negotiate terms. City Council also met at the Castle Frank table to go over the boundaries of what would be park and what would be cemetery; property owners, led by Mr. Jackson of Drumsnab, were there to protest. By November, talks between the city and cemetery had broken off as the city found the trustees unreasonable in their terms. The cemetery in the meantime began to make arrangements with Dr. Hoskins to bury in the property they did own. Eventually the scheme was dropped entirely by the city. The matter was finally reopened in the following October with new negotiations.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

In December 1898, the Globe reported the City had finally reached an agreement with St. James Cemetery to add forty-two acres of parkland in the Rosedale Ravine. At a special Board of Control meeting to discuss the plan, Mr. Jackson again argued his objections, stemming from a loss of taxes on would-be property, the need for a clause to compensate property owners, and a letter from medical men advocating that cemeteries should not be established within city limits. The agreement was referred to council.

By early 1899, it was advertised The McIntosh Granite and Marble Co. a mausoleum built on the Castle Frank section of the cemetery for a W.R. Brock, Esq. In July, the city and cemetery entered into an agreement for the city to lease some cemetery property for parkland in return for permission to bury in Castle Frank. It was opposed by a Mr. J. G. Ramsey who owned property at Castle Frank and Mackenzie Avenues and argued it would “render his property comparatively valueless.” A very animated Mr. Jackson also spoke against it. The plan was sent to council without recommendation as no consensus was reached.

Source: The Globe & Mail Archives

Curiously, as the city moved into the twentieth century, the records are silent on what happened next regarding this contentious episode. It must be noted that by the end the decade and into the 1910s, houses began to sprang up on Castle Frank Avenue on the ridge and there are no references to the cemetery. The City of Toronto today lists the area south and east of the street as parkland.

Source: Goads Toronto

The Bloor Viaduct

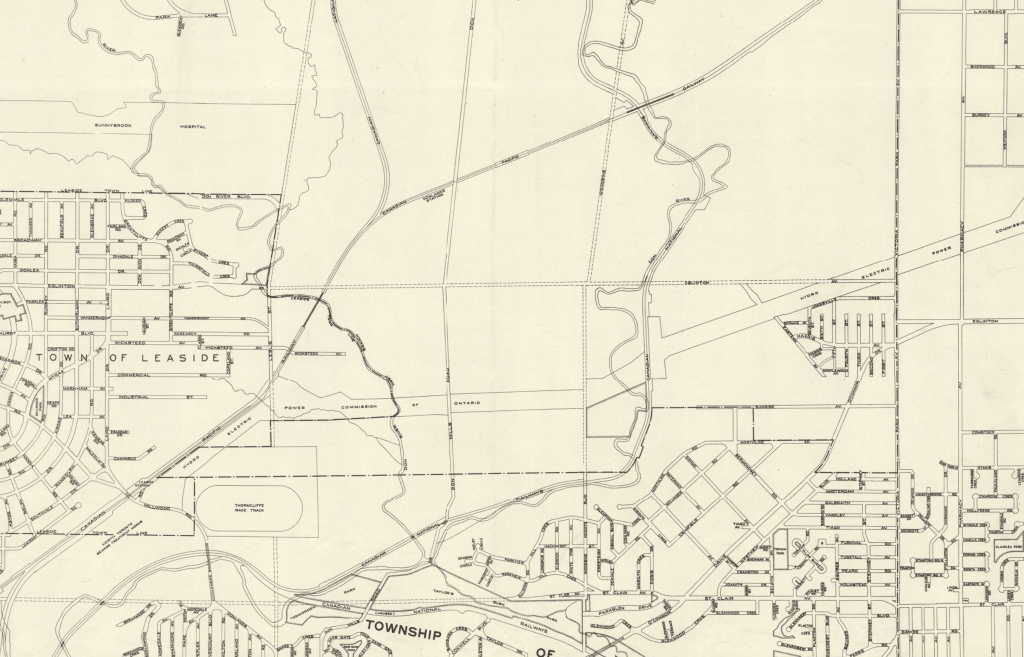

While the earliest mention of a bridge across the Don Valley joining Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue was in 1897, proposals on how to make it happen came about in the following decade. With the likely need to traverse Rosedale Valley as well, Castle Frank Hill would become an important part of the project. One idea involved two bridges running west and east from Castle Frank Crescent, connecting with Howard Street over Rosedale Valley and Winchester Street over the Don Valley, respectively. However, a prominent idea was put forward by City Engineer C.H. Rust which recommended a one mile-long bridge straight from Sherbourne Street to Broadview Avenue and another shorter viaduct extending from Parliament Street to meet it a “T”. Arguments over the impact it would have on Rosedale Valley by the Guild of Civic Art and Civic Improvement Committee as well as Rosedale resident concerns led to a “no” vote in referenda in 1910, 1911, and 1912.

Sources: The Toronto Daily Star, Nov 28, 1906; The Toronto Daily Star, June 6, 1917; The Globe, Dec 29, 1910; The Globe Dec 28, 1911; The Globe Jan 1, 1913

On January 1, 1913, the Toronto electorate voted to finally build the Bloor Viaduct. Construction began officially in 1915, although preliminary work was done in the years that preceded. The eventual design relied on two separate bridges to cross both ravines as well as the extension of Bloor Street between Sherbourne and Parliament Streets, which would be facilitated by landfill terraces. The bridges consisted of a ‘diagonal’ Rosedale section between Parliament to Castle Frank and a ‘straight’ Don section between Castle Frank and Broadview Avenue. Both sections were similar in aesthetic, made of concrete and steel, and highlighted by large arches. A lower level for a future streetcar line was added to both bridges. The bridge opened in sections with the entire structure – officially The Prince Edward Viaduct – being available on October 18, 1918.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Source: City of Toronto Archives

The eventual changes to the geographic imprint of the area extended past just the additions of the new bridges and roads. In order to facilitate those additions, several losses had to take place. There were several residences razed for the Bloor Street extension, including the Castle Frank gatehouse at Parliament Street, its neighbour at 102 Howard Street, and other structures at Glen Road and Sherbourne Street. On the Castle Frank Hill, it appears that at least one or two residences on Castle Frank Road — such as number 87 — were lost where the new street was set to go in and parts of other lots gave way for the new street layout. In 1922, Castle Frank Road south of the Bloor Viaduct was renamed to Castle Frank Crescent (ironically, a name it once held before it was combined into Castle Frank Road).

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Source: Goads Toronto

The Don Valley Parkway & The Destruction of Sugar Loaf Hill

The middle of the 20th century saw a string of major civic projects which would collectively change the local complexion of the Castle Frank Region. The first of these was a freeway through the adjacent Don Valley. Planning began in 1954. This would be a different kind than the parkway built through the Rosedale Valley nearly sixty years prior. In the lower valley, the project consisted of the main highway which would run on the east side of river and the southern extension of Bayview Avenue running parallel to it on the west side of the river beside the train tracks.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A product of the creative destruction of the Don Valley Parkway was the removal of Sugar Loaf Hill, the conical mound located north of Castle Frank that the Simcoes, E.T. Seton, and Charles Sauriol all noted and explored. It would be levelled to make way for the Bayview Extension. Several lamenting articles appeared in newspapers over the event. In 1958, during the construction of the highway, Globe writer Scott Young wrote:

“Soon it will be gone and fast bright cars on the Don Valley Parkway will stream north and south over one more vanished place where boys once roamed alone, every step an adventure, and even the crows had names.”

Scott Young, The Globe and Mail, May 8, 1958

Young also spoke to Charles Sauriol about the loss:

“As he says, nobody seriously contends that a hill that few people ever even look at, or use much (although a worn path twisting to Sugar Loaf’s top ends now suddenly in the wake of a bulldozer) should stand in the way of a needed roadway.

Yet it is an item of history. Going, going, gone.”

Source: City of Toronto Archives

Young, like Ron Haggart writing for the Toronto Daily Star, referenced E.T. Seton and Silverspot. Haggart was writing on the eve of the opening of the Don Valley Parkway in August 1961:

It will be open in time for the afternoon rush hour. And, not seeing with the same eyes as Ernest Thompson Seton, we can drive over the 137,000 tons of asphalt which now lay in the Don Valley, skirting the Don River bright with the chemicals of the paper mill under the 600 towers of the fluorescent lighting standards, which never will house an old hawk’s nest known by every school boy.

‘I’ll tell you what the Don Valley was,” Frederick Gardiner said once, when someone on his Metropolitan council, mourned for the passing of the woods by Castle Frank, “the Don Valley was a place to murder little boys, that’s what it was”

Ron Haggart, The Toronto Daily Star, August 30, 1961

Frederick “Big Daddy” Gardiner was the Chairman for Metro Toronto Council and was a bold and controversial figure who was involved in several public works projects, including the Don Valley Parkway and the elevated downtown highway which would later bear his name.

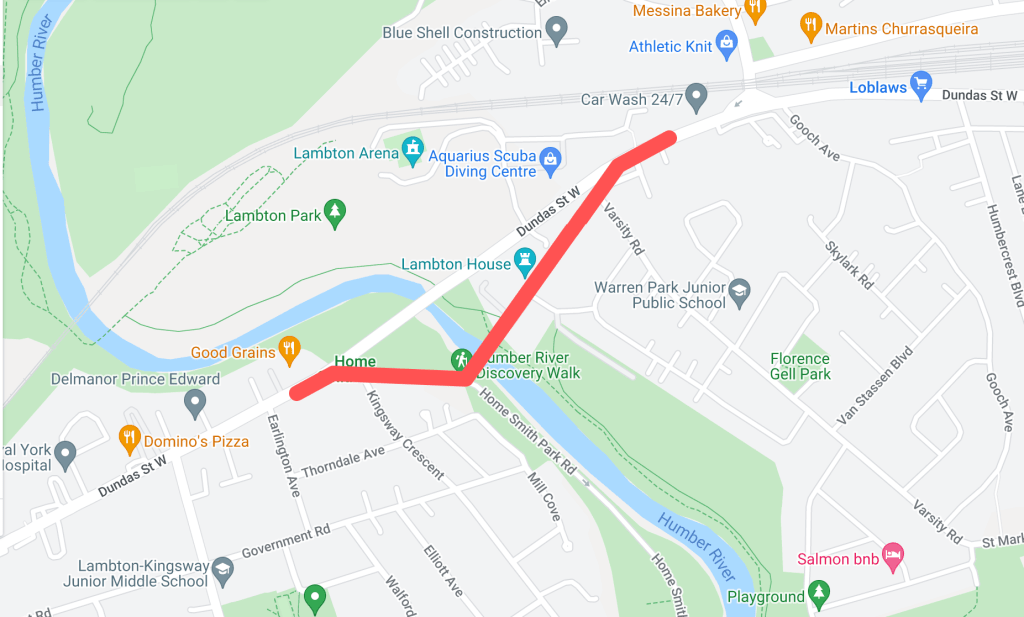

The DVP’s other impact was a long offramp for the Bayview/Bloor exit that would wind its way across the valley and down to Castle Frank Road. The ramp would absorb part of the Drumsnab property (the old estate house is visible on the right as one drives south on the ramp) as well as part of Drumsnab Road.

Source: City of Toronto Archives

A New Subway

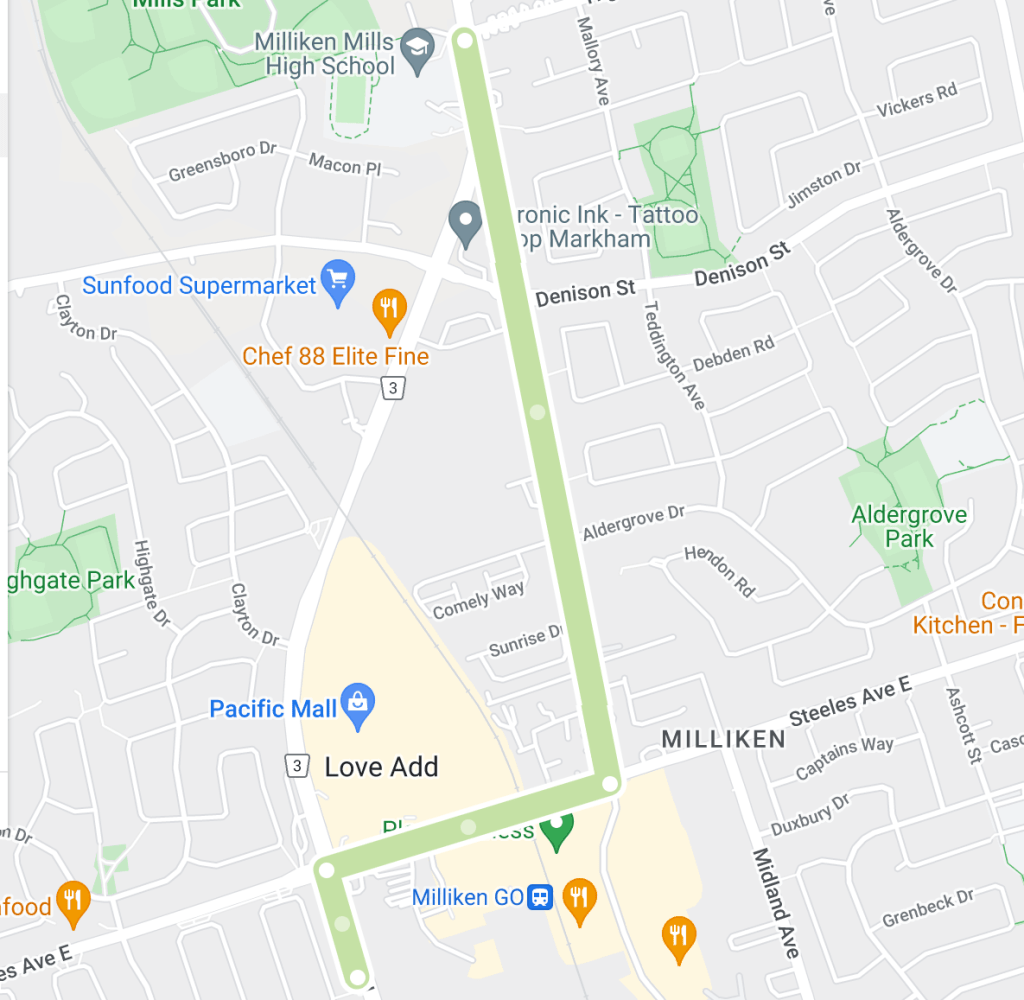

The next time a major infrastructure project touched Castle Frank was in the 1960s, when an east-west, cross-town subway line was planned for Toronto. With the Bloor-Danforth corridor ultimately chosen for the project, decisions would need to be made about how it would cross the Don and Rosedale Valleys and a location for the station itself. Construction began in 1962.

As a cost-cutting method, the route was chosen to run under the lower deck of the existing viaduct. At least, it would be on the Don section. The turns on the Rosedale section were deemed too sharp for trains. Thus, a separate structure – a covered bridge – ran between Castle Frank Station and the infilled Bloor Street over Rosedale Valley. The elevated tunnel was encased to minimize noise concerns for the nearby Kensington Apartments (which were incidentally built on the site of John Hoskin’s Dale, demolished in the 1940s or 50s).

Source: City of Toronto Archives

The station itself was built on the northwest corner of Bloor Street East and Castle Frank Road. At least four residences were removed to make space for the station and a bus station. The station opened on February 26, 1966 along with the rest of the line.

The Castle Frank School

Lady Kemp passed away in 1957, twenty-eight years after her husband, Sir Edward Kemp. Their palatial Castle Frank was put up for sale; executors of her estate put a sale price of $1.2 million. The City of Toronto, Metro Council, and the Toronto Transit Commission turned down opportunities – likely because of the price tag – to turn the site into a park, a parking garage, or a subway station. The Toronto Civic Historic Society pitched to Ontario Premier Frost to turn it into a residence for the Lieutenant-Governor. It was also proposed as a museum for York County.

The emerging proposal came from prolific Toronto developer Reuben Dennis in late 1958. His vision was to raze the mansion to erect a 21-storey, 972-unit luxury apartment building. Residents of Castle Frank Crescent, whose homes backed onto the property, opposed the rezoning of the single-family residential area. The affected residents included some of Canada’s most prominent citizens, such as former Prime Minister Arthur Meighen, Mr. Justice Gibson of the Ontario Court of Appeal, Lew Haymen, the managing director of the Toronto Argonauts, and Mrs. H..J. Cody, the wife of the late former president of the University of Toronto. The residents – who called the plan “ghastly, revolting, and a great pity” – organized into the South Rosedale Ratepayers. The battle continued in 1959 with the Toronto Planning Boarding rejecting the application and the Ontario Municipal Board being asked to change the zoning.

Source: Globe and Mail Archives

By July 1960, Castle Frank was back on the market. The new plan was for a vocational type school for a “lower middle group of secondary school-age pupils and others who do not plan to go university.” The Kemp estate accepted a $700,000 offer. The Globe and Mail described:

In the beginning, Castle Frank will operate with an experimental program designed to build up an approved curriculum for its 500 students. The new Boulton Avenue School could become the second of this type in Toronto.

Castle Frank and the junior vocational schools are based on the concept that slow learning or emotionally disturbed pupils have a special place in a modern society with a rapidly changing technology.

Castle Frank also takes into account that there are many intelligent students who do not want to go to university and need some educational medium other than the existing academic, technical or commercial high school

The Globe and Mail, November 17, 1960

Castle Frank School was opened in 1963. It operated until the 1990s when “an organized abandonment” led to a change in model. A rebrand in name also came with the move: Rosedale Heights Secondary School, later Rosedale Heights School For the Arts. The institution that stands today, housing a salvaged piece of the Kemps’ residence and a plaque. The principal at the time of the shift hoped to name the new school after Elizabeth Simcoe.

Remembering Castle Frank

Today, the Simcoes’ 1790s summer residence is honoured in name by Castle Frank Road, Castle Frank Crescent, and Castle Frank Subway Station. In 1954, the Don Valley Conservation Authority (of which Charles Sauriol was a member) erected a cairn dedicated to Castle Frank in Prince Edward Viaduct Parkette on the south side of Bloor Street. The monument dons the image of the home and reads:

“Castle Frank

The country home of Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada 1791-1796, stood on these heights just south of this site 1794-1829. Named after Francis Gwillim Simcoe, son of Lieutenant Governor and Mrs. Simcoe, who died in the year 1812, serving under the Duke of Wellington.”

Source: Google Maps

The Ontario Heritage Trust also erected one of their iconic blue plaques in honour of Elizabeth Simcoe. It stands inside the grounds of the Rosedale Heights School, which might have bore her name at one time. The plaque says:

“ELIZABETH POSTUMA SIMCOE 1766 – 1850

The wife of the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim was born at Whitchurch, Herefordshire, England. Orphaned at birth, she lived with her uncle, Admiral Samuel Graves, and subsequently married his god-son, John Graves Simcoe. She accompanied her husband to Upper Canada where she travelled extensively. Her diaries and sketches, compiled during these years, provide a vivid description and invaluable record of the colony’s early life. In 1794, near this site, Mrs. Simcoe and her husband erected a summer house which they named “Castle Frank” in honour of their son. Returning to England in 1796, Mrs. Simcoe devoted her later years to charitable work. She is buried beside her husband at Wolford Chapel, Devon.”

Castle Frank, in its post-contact era, began as a beautiful hilltop locale, hand-picked by Toronto’s top administrator to house his residence. The layers of activity over the next two centuries continued to prove its desirability, facilitated in part by its central location and unique situation between two valleys. These commemorations mark a place and people important to the early colonial history of Toronto. The events that point in time added intriguing layers which together tell an interesting story.

Sources Consulted

“About The City.” The Globe, 3 June 1890, p. 8.

“Apartments Planned for Historic Site.” The Globe and Mail, 18 Dec. 1958, p. 5.

“Ask OMB to Amend Castle Frank Zoning.” The Globe and Mail, 30 Oct. 1959, p. 4.

Bateman, Chris. “That Time Toronto Opened the Don Valley Parkway.” blogTO, blogTO, 10 Aug. 2013, http://www.blogto.com/city/2013/08/that_time_toronto_opened_the_don_valley_parkway/.

Bateman, Chris. “The Modernist Bloor-Danforth Line at 50.” Spacing Toronto, 25 Feb. 2016, spacing.ca/toronto/2016/02/25/subway-modern-at-50/.

Berchem, F. R. The Yonge Street Story: 1791-1860: An Account from Letters, Diaries and Newspapers. Natural Heritage/Natural History, 1996.

“The Bloor Street Viaduct.” The Globe, 13 June 1913, p. 6.

“The Bloor Viaduct Conference.” The Globe, 19 Jan. 1912, p. 6.

Bonnell, Jennifer. Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley. University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Boylen, John Chancellor. The Story of Castle Frank, by J.C. Boylen. Illus., from Original Sketches Painted by Mrs. John Graves Simcoe.

Brace, Catherine. “Public works in the Canadian city; the provision of sewers in Toronto 1870–1913.” Urban History Review, vol. 23, no. 2, 1995, pp. 33–43, https://doi.org/10.7202/1016632ar.

Cabbagetown Uncovered: Simcoe Family Built Castle Frank … – Toronto.Com, http://www.toronto.com/news/cabbagetown-uncovered-simcoe-family-built-castle-frank-in-the-wilderness-near-the-don-river/article_77f1bdbc-722d-54d4-b638-d34a0ca2b7d4.html. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

“Canada.” The Globe, 13 Sept. 1871, p. 4.

“Castle Frank Apartment Plan Turned Down.” The Globe and Mail, 6 May 1959, p. 5.

Castle Frank, http://www.lostrivers.ca/points/CastleFrank.htm. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

Caswell, Thomas. “Notice Is Hereby Given.” The Globe, 21 Jan. 1899, p. 8.

“Cemetery Deal Off.” The Globe, 1 Nov. 1897, p. 5.

“The City Is Leading.” The Evening Star, 18 Nov. 1897, p. 1.

City of Toronto. “Bridging the Don: The Prince Edward Viaduct.” City of Toronto, 14 Apr. 2023, http://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/online-exhibits/web-exhibits/web-exhibits-architecture-infrastructure/bridging-the-don-the-prince-edward-viaduct/.

“City’s Proposed Plan For Crossing The Rosedale Ravine – And Another.” The Globe, 29 Dec. 1910, p. 7.

“Colleges Free of Taxes.” The Globe, 22 Oct. 1897, p. 5.

Commemorative Biographical Record of the County of York, Ontario: Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens and Many of the Early Settled Families, Illustrated. J.H. Beers, 1907.

“Company Plans Caste Frank Veto Appeal.” The Globe and Mail, 14 May 1959, p. 5.

“Council Must Decide.” The Globe, 21 Oct. 1897, p. 5.

“Council Passes St. Lawrence Market Report.” The Evening Star, 21 July 1899, p. 8.

Don River Valley Historical Mapping Project, maps.library.utoronto.ca/dvhmp/castle-frank.html. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

Early Canada Historical Narratives — John Graves Simcoe, http://www.uppercanadahistory.ca/simcoe/simcoe1.html. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

“Evocative Images of Lost Toronto.” UrbanToronto, UrbanToronto, 19 Nov. 2023, urbantoronto.ca/forum/threads/evocative-images-of-lost-toronto.11018/page-170.

“The Expensive By-Law Plan, and Another.” The Globe, 28 Dec. 1911, p. 7.

Filey, Mike. Toronto Sketches 3: “The Way We Were.” Dundurn Press, 1994.

“Finds Building Apartments Fascinating Job.” The Globe and Mail, 27 Oct. 1959, p. 18.

“A Fine New Park.” The Evening Star, 11 Oct. 1898, p. 8.

“For A Drive in Rosedale.” The Globe, 11 Dec. 1905, p. 7.

“For Public Park.” The Globe, 10 Dec. 1898, p. 17.

“For Sale.” The Globe, 1 Jan. 1857, p. 4.

“Governments Share Costs of Castle Frank School.” Toronto Daily Star, 29 Mar. 1961, p. 39.

Haggart, Ron. “Earnest Thompson Seton And The New Parkway.” Toronto Daily Star, 30 Aug. 1961, p. 7.

Hamilton, James Cleland. Osgoode Hall–Reminiscences of the Bench and Bar. Nabu Press, 2010.

Henderson, Elmes. “BLOOR STREET, TORONTO, AND THE VILLAGE OF YORKVILLE IN 1849 .” PAPERS AND RECORDS, Ontario Historical Society, XXVI, 1930, pp. 445–456.

“Here’s A Pretty Mess.” The Globe, 2 Nov. 1898, p. 8.

“A Historic Landmark.” The Globe, 28 Mar. 1928, p. 4.

“Horses and Cemetery.” Toronto Daily Star, 3 Feb. 1905, p. 7.

“In Commitees.” The Globe, 10 Mar. 1899, p. 8.

“In Committee.” The Globe, 8 Mar. 1899, p. 4.

Information Regarding Doctor John Hoskin K. C. , L. L. D. & His/Her Family, harris-history.com/tree/2226.html. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

Jones, Morland. “Fight Seen Over Historic Site: Plan to Raze Castle Frank Estate For 21-Story Luxury Apartments.” The Globe and Mail, 18 Dec. 1958, pp. 1–2.

“Lady Kemp’s Will $481,549, Kin to Get Husband’s 7,718,000.” Toronto Daily Star, 1 Oct. 1957, pp. 1–2.

“Lamb on the Defensive.” The Globe, 21 Sept. 1897, p. 5.

“The Law and the Graves.” The Evening Star, 19 Oct. 1897, p. 1.

“Letter to Sir Joseph Banks (President of the Royal Society of Great Britain) Written by Lieut.-Governor Simcoe, in 1791, Prior to His Departure from England for the Purpose of Organizing the New Province of Upper Canada.” Google Books, Google, http://www.google.ca/books/edition/Letter_to_Sir_Joseph_Banks_president_of/TZUOAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22parliament%2Bstreet%22%2B%22castle%2Bfrank%22&pg=PT3&printsec=frontcover. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

“Link to the Past Severed by Death.” The Toronto Daily Star, 28 July 1927, p. 9.

“Local News.” The Globe, 26 Apr. 1887, p. 8.

Lundell, Liz. The Estates of Old Toronto. Boston Mills Press, 1997.

MacIntosh, Robert. Earliest Toronto. General Store Pub., 2006.

“Madge Merton’s Page.” The Toronto Daily Star, 22 Sept. 1900, p. 12.

“Minutes of Proceedings of the Council of the Corporation of the City of Toronto.” Google Books, Google, books.google.ca/books?id=tr1EAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA3-PA510&dq=bloor%2Bviaduct%2Bexpropriation&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj-3Za9s5eDAxW3BDQIHY__Bs8Q6AF6BAgKEAI#v=onepage&q=bloor%20viaduct%20expropriation&f=false. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

Murnaghan, Ann Marie. “The city, the country, and Toronto’s Bloor Viaduct, 1897–1919.” Urban History Review, vol. 42, no. 1, 2013, pp. 41–50, https://doi.org/10.3138/uhr.42.01.03.

Murnaghan, Ann. “The City, the Country, and Toronto’s Bloor Viaduct, 1897–1919 – Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire Urbaine.” Érudit, Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine, 3 Feb. 2014, http://www.erudit.org/en/journals/uhr/2013-v42-n1-uhr01125/1022058ar/.

“‘Never Wanted to Do Anything Else’: Toronto Principal Marks 40+ Years at the Helm.” Toronto, CTV News, 2 May 2023, toronto.ctvnews.ca/never-wanted-to-do-anything-else-toronto-principal-marks-40-years-at-the-helm-1.6380455.

“New Homes in Toronto.” The Globe, 18 Jan. 1913, p. A1.

“The New Market.” The Globe, 13 July 1893, p. 7.

“New Plan to Bridge The River Don.” The Toronto Daily Star, 17 June 1907, p. 6.

“Now The Market.” The Globe, 14 July 1899, p. 6.

“Opposes The Park.” The Evening Star, 14 Dec. 1898, p. 1.

Osbaldeston, Mark. Unbuilt Toronto a History of the City That Might Have Been. Dundurn Press, 2008.

“The Parks Plan.” The Evening Star, 17 July 1897, p. 5.

“Parks The City Should Have.” The Toronto Star, 17 July 1897, p. 4.

“Parliament Buildings of Ontario.” The Globe, 30 May 1893, p. 4.

“Plan for the Proposed Bloor Street Viaduct.” The Globe, 1 Jan. 1913, p. 8.

“Preparation Are Made For Bloor Street Viaduct.” The Globe, 2 June 1914, p. 9.

“Ravine Bridge Scored.” The Globe, 22 Dec. 1909, p. 5.

“The Ravine Drives.” The Globe, 5 Mar. 1887, p. 16.

READ, D. B. Life and Times of Gen. John Graves Simcoe: Commander of the “Queen’s Ranger’s” during the… Revolutionary War, and First Governor of Upper Can. FORGOTTEN BOOKS, 2018.

“Real Estate Now Is Satisfactory.” The Toronto Daily Star, 19 Jan. 1901, p. 7.

“Revised Subway Plan Approved by Board.” The Globe, 29 Oct. 1960, p. 3.

Robertson, J. Ross. Landmarks of Toronto: A Collection of Historical Sketches of the Old Town of York from 1792 until 1833, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1898. Mika, 1974.

“Rosedale and the Cemetery.” The Globe, 18 Sept. 1897, p. 20.

“Rosedale and The Cemetery.” The Globe, 25 Sept. 1897, p. 6.

“Rosedale Valley Drive.” The Globe, 11 Nov. 1898, p. 4.

Sauriol, Charles, and Vivian Webb. Tales of the Don. Natural Heritage/Natural History Inc., 2016.

Sauriol, Charles. Remembering the Don: A Rare Record of Earlier Times within the Don River Valley. Consolidated Amethyst Communist Communications, 1981.

Scadding, Henry. Supplement to Rev. Dr. Scadding’s Story of Castle Frank, Toronto. 1896.

“Seeking A Route For The Viaduct.” The Globe, 29 Jan. 1912, p. 9.

Senter, James. “Vocational-Type School Planned for Castle Frank Site: Estate Accepts $700,000 Offer.” The Globe and Mail, 10 Nov. 1960, p. 5.

Seton, Ernest Thompson. Wild Animals I Have Known. Gibbs Smith, 2020.

Simcoe, Elizabeth, and Mary Quayle Innis. Mrs. Simcoe’s Diary. Dundurn, 2007.

Smith, Anne. “‘Let’s Keep What’s Left of Rosedale.’” The Globe and Mail, 24 Dec. 1958, p. 6.

“Special Committee Approves: Replacement Planned for Boulton.” The Globe and Mail, 17 Nov. 1960, p. 5.

St. John, J. Bascom. “THE WORLD OF LEARNING: PROGRAM FOR DROPOUTS.” The Globe and Mail, 14 May 1964, p. 7.

“Story of Castle Frank.” The Globe, 8 May 1895, p. 6.

“That New Hotel.” The Globe, 1 July 1899, p. 32.

“Three Proposals to Cross Ravines to North-West Section.” The Toronto Daily Star, 28 Nov. 1906, p. 8.

Toronto of Old, by Henry Scadding – Gutenberg, gutenberg.ca/ebooks/scadding-torontoofold/scadding-torontoofold-00-h-dir/scadding-torontoofold-00-h.html. Accessed 4 Jan. 2024.

“Two Contracts For Subway Are Awarded.” The Globe and Mail, 16 Jan. 1963, p. 4.

“Two Streets, But One Name.” The Globe, 26 Sept. 1922, p. 13.

“Under Rough Roof, Gay Days: Cairn to Mark Site Of Simcoe’s Castle.” The Globe and Mail, 6 Mar. 1954, p. 10.

“W.A. Murray & Co.” The Globe, 2 Jan. 1899, p. 7.

Westall, Stanley. “Metropolitan Toronto: A Castle on Bloor St.” The Globe and Mail, 28 July 1960, p. 7.

“Will Fight Rezoning Of Castle Frank Area.” The Globe and Mail, 11 Feb. 1959, p. 5.

“A Winchester Viaduct.” The Globe, 3 Feb. 1912, p. 6.

“Would Buy Land For Viaduct.” The Globe, 26 Mar. 1912, p. 9.

“Writing the Environmental History of Toronto’s Don Valley Parkway.” Jennifer Bonnell, jenniferbonnell.com/writing-the-environmental-history-of-torontos-don-valley-parkway/. Accessed 3 Jan. 2024.

YEIGH, FRANK. Ontario’s Parliament Buildings: Or a Century of Legislation, 1792-1892. FORGOTTEN BOOKS, 2018.

“York Pioneers.” The Globe, 1 Feb. 1870, p. 1.

Young, Scott. “In the Road: Sugar Loaf Soon Thing Of Memory.” The Globe and Mail, 8 May 1958, p. 27.