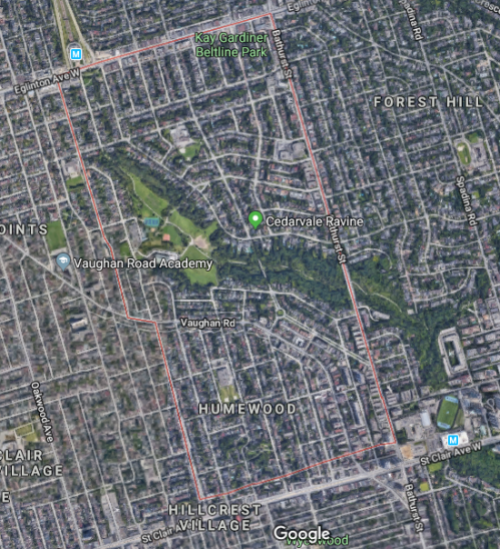

Cedarvale lies northwest of the intersection of Bathurst Street and St. Clair Avenue West in the old City of York. At the centre of its story and its geography is its parkland. All that surrounds is just as interesting.

Mappy beginnings

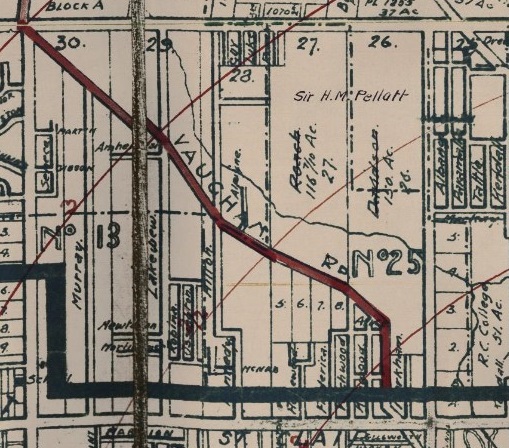

The history of Cedarvale begins with lots 26 and 27 of Concession III west of Yonge Street from the old lot system. The third concession road is now the mentioned St. Clair West with the 200-acre lots extending north to the fourth concession (Eglinton Avenue) just west of present Bathurst Street.

Lot 27 first appears in Toronto maps as belonging to the Estate of James Brown. It then passed to John Roach. Lot 28 belonged to a John Severn and then to a Mr. Davidson. The 1899 and 1903 editions of the Goads Fire Insurance Maps show brick fields near Markham Street (today’s Raglan Avenue) which are gone by 1910. Flowing diagonally through the plots was Castle Frank Brook, making brick manufacturing a possibility. The stream was also known as Brewery Creek or Severn Creek, as it is the same waterway that aided the Severn Brewery in Yorkville. It is unclear if the brewer and the land owner are the same, but it is notable their given names do match. By the 1910s, the plots appear under the name of Sir Henry Pellatt of Casa Loma fame.

A New Subdivision

Situated up Bathurst at Claxton Boulevard is the first curiousity about this unique area: the Connaught Gates. Dating to 1913, they hide an ambitious past.

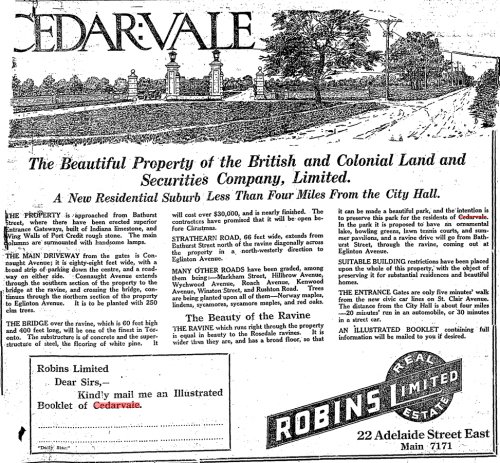

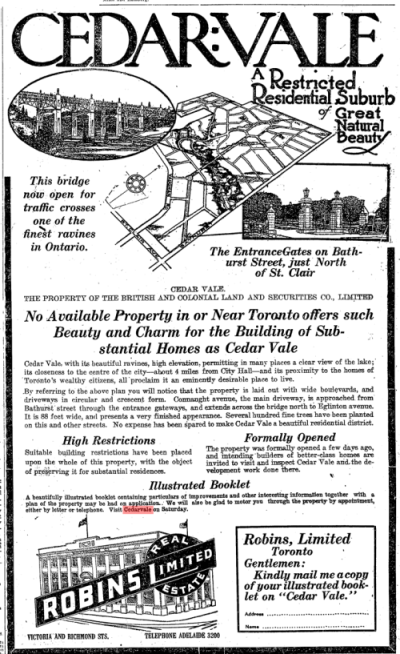

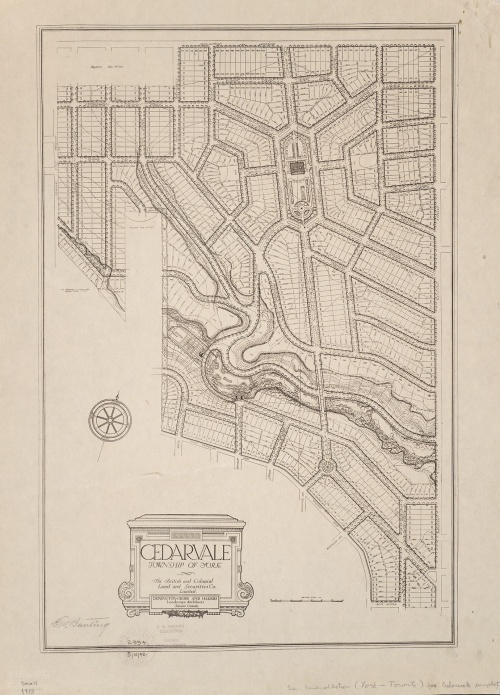

Beginning in June 1912, advertisements in The Toronto Daily Star and The Globe newspapers promoted a new exclusive suburb named Cedarvale (or Cedar Vale) in the area south of Eglinton Avenue, north of Vaughan Road, and west of Bathurst Street. The company behind the new 300-acre subdivision was The British and Colonial Land and Securities Company, which was Sir Henry Pellatt’s realty firm. Pellatt’s interests were in land accumulation and speculation. The sales pieces marketed Cedarvale’s tree-lined streets including a neighbourhood-spanning central boulevard and a natural beauty even surpassing Rosedale in the form of Cedarvale ravine. Interested parties were to contact Robins Real Estate Limited for an illustrated booklet.

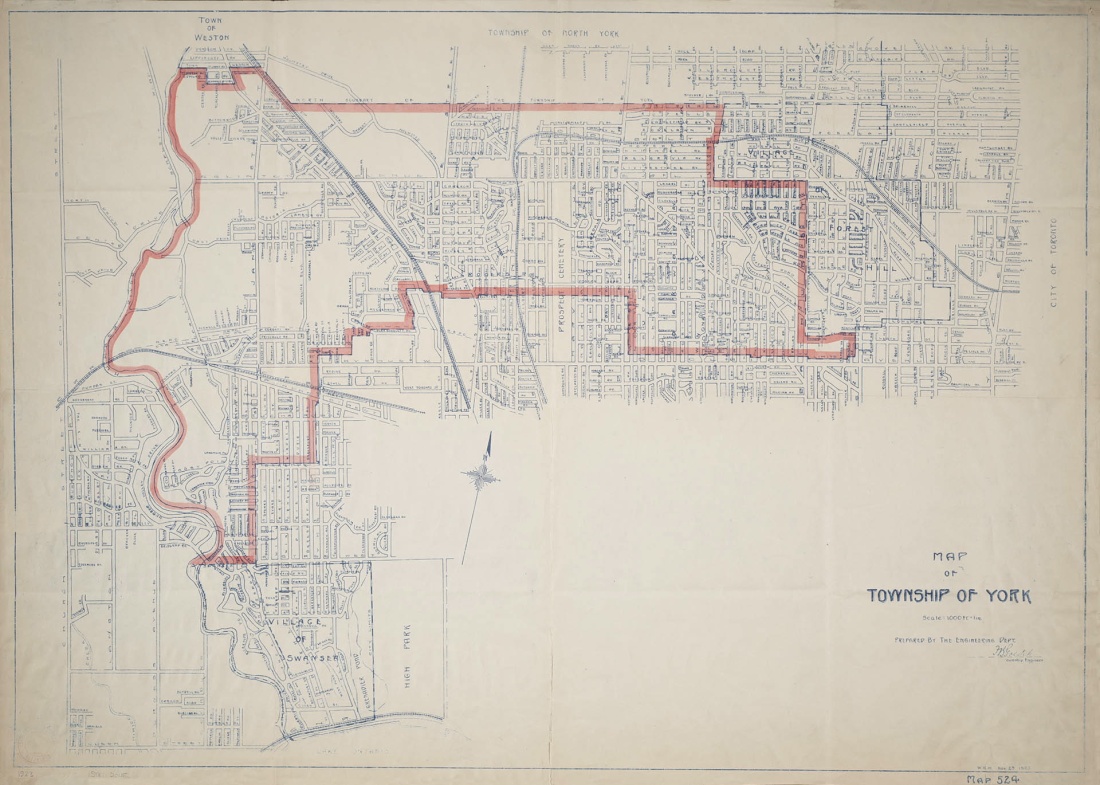

Contextually, Cedarvale’s emergence came at a time in the early 20th century when civic discussions revolved heavily around the growth of the city of Toronto and its surrounding areas. Annexations of neighbouring St. Clair Avenue communities of Wychwood and Bracondale in 1909 and Dovercourt and Earlscount in 1910 increased the city’s borders. In the following year, the Toronto Civic Railways opened a transit line along St. Clair, effectively turning those communities into streetcar suburbs and spurring development. Cedarvale – which took advantage of the new streetcar in their new promotional pieces – joined these discussions of annexation, which included a November 1912 meeting of Pellatt, John Gibson, and other investors with Toronto mayor Horatio Hocken. Although the benefits of extending city services like sewers and police and fire protection were discussed, Cedarvale ultimately stayed in the Township of York, not joining Toronto until the mega-city amalgamation in 1998.

The original vision of Cedarvale centred around Connaught Avenue. From the gates at Bathurst, the street travelled northwest, passing through the Connaught Circle roundabout. It then spanned over the valley with the mighty Connaught Bridge. The bridge was important in connecting the upper and lower parts neighbourhood, an affinity still valued today. From here, Connaught spilt into east and west sections, surrounding a diamond island of gardens, finally terminating at Eglinton. Surrounding streets, including one named Pellatt Crescent, fed into the Connaught Gardens. Ravine Drive followed the valley below with lots for purchase. Running adjacent was a trail as well as a lake and tennis courts which could be accessed from the path or via stairs from Hillbrow and Roach Street (Heathdale and Humewood Street today). They would have been located where the Cricket Field and Phil White Arena stand today.

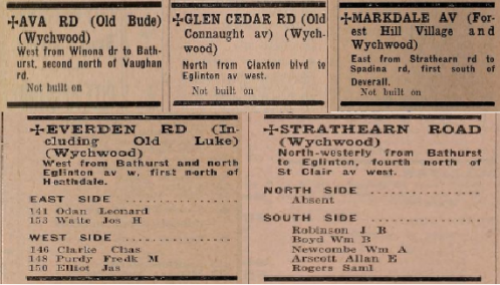

By the 1930s, maps show a street grid which curiously deviates from the original vision, looking closer to the present-day neighbourhood. Connaught Gates and Connaught Circle still showed, but Connaught Gardens disappeared from the grid. The street was also renamed Claxton Boulevard and Glen Cedar Road, north and south of Connaught Circle respectively. It is notable here that Sir Henry Pellatt himself went bankrupt in 1923 after some shady dealings of buying land and borrowing money, and the street baring his name failed to exist.

Development in the 1930s to 1950s

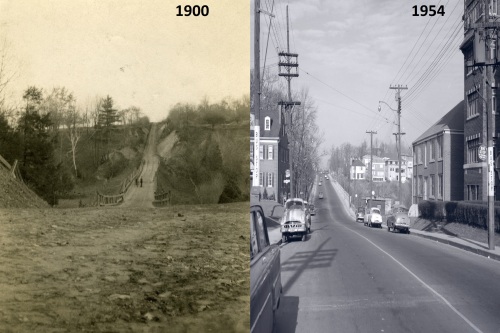

Cedarvale’s streets began to modernize in the 1930s as its population grew and changed, and the city’s geographies necessitated better connectivity. Housing south of the valley had developed in the 1920s, but north of the valley, development stalled. As a point, Glen Cedar Road was not built on at all in 1930. The answer to this: A new $250,000 bridge opened on Bathurst Street on August 6, 1930, replacing an earlier muddy construction over Cedarvale Ravine. The move opened the entire area for development in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s.

A specialty to York Township, which lacked the building restrictions of Toronto, Bathurst Street between St. Clair and Eglinton Avenues became a sort of ‘apartment row’ in the inter-war years, providing the home to new residents. Architect Victor Llewellyn Morgan designed a few of these walkup lofts, including the 1931 Claxton Manor. Wordsmiths Northrop Frye and Ernest Hemingway also famously resided in Bathurst Street lofts.

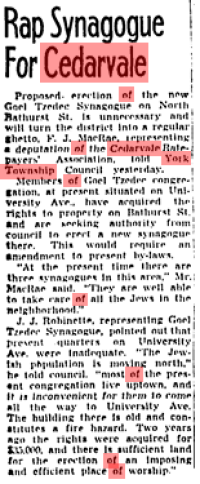

By the 1950s, the Jewish community also moved north from downtown Toronto. The Goel Tzedec Congregation, whose synagogue was situated on University Avenue, looked to Bathurst Street North for a new site. Despite community opposition, York Township Council had approved the erection of a place of worship in September 1949. After a merger with the Beth Hamidrash Hagadol Congragation, Beth Tzedec Synagogue was dedicated on December 9, 1955.

Cedarvale Ravine

With numerous access points, Cedarvale Park is well connected to the neighbourhood as it was originally intended. The space itself can be thought of in two sections. To the north, there is an open field area with panoramic views to the downtown Toronto skyline.

To the south, the park is a more wooded and wetland area with the overhead sights of valley-backing houses and the towering bridges of Glen Cedar and Bathurst. Castle Frank Brook also makes its appearance here, albeit briefly. In the 1910s, one could witness military demonstrations in the valley; in the 1920s, Ernest Hemingway is said to have meandered its grounds. But as much as Cedarvale Ravine is about the beauty all around, its story is as much about what is underneath — and what might have existed above.

Spadina Subway/Expressway

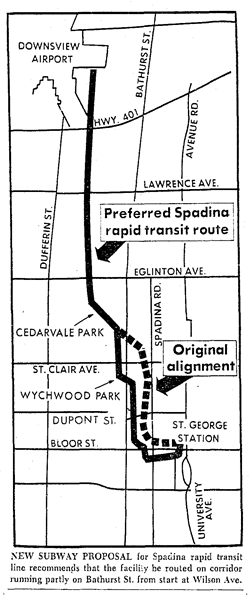

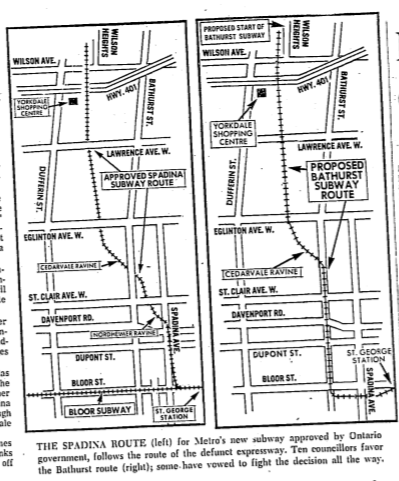

Talk of a northward extension of Spadina Road began in the 1950s with formal plans by the Ontario Government announced in the 1960s. In June 1971, after serious community opposition, Ontatio Premier William Davis cancelled the controversial Spadina Expressway, halting construction at Lawrence Avenue. This threw rapid transit plans up in the air, specifically the Spadina subway that would have ran along the highway. Since a highway would not happen, the route of the subway fell under debate. Under the original plans, the subway would have run from Downsview Airport through the ‘Spadina corridor’ south to Eglinton and then through Nordheimer and Cedarvale Ravines to Spadina Road, where it would join with Bloor Street at St. George Station. A new proposal favoured a route under Bathurst Street to the Bloor-Danforth Subway.

Metro Toronto Council established a task force to determine its possibilities. The task force analyzed more than 10 possibilities and narrowed it down to 5 final routes. Two of the routes were variations on the original Spadina corridor; the other three followed Bathurst Street. All five designs recommend leaving the portion from Wilson Station to Eglinton untouched.

The ‘winning proposal’ had the subway cutting under Cedarvale ravine, then under Claxton and Raglan Avenues, under Bathurst, then south on Albany to Bathurst station, then bypassing Spadina Station to join with St George. It was chosen because of the possibilities to extend the subway south of Bloor to join Queen and to the waterfront. The downsides though were the requirement of acquiring 150 more properties and the demolition of 85 more houses, and would require construction on Bathurst.

Proponents of the Spadina Expressway opportunistically favoured the original alignment because it meant that the Expressway could be added later. The borough of York – and the Cedarvale community specifically – did not favour either for the damage it would do to the ravine and for the expropriated properties. Preparations in 1971 had already interrupted recreational activities in the park. Debate continued into 1972. The Spadina line was a much needed relief line for the Yonge subway, which, even though was set to extend to York Mills from Eglinton in 1972 and to Finch in 1973, was at capacity. A decision was needed.

Finally in January 1973, Premier Davis announced that it would fund 75% of the cost of the subway. It was up to Metro to decide the route of the subway. Council voted in favour of the Spadina alignment for its lower cost and construction time. The Borough of York agreed to support the subway under the grounds that the proposed Bathurst station at Heathdale would be nixed.

Toronto City Council opposed the vote and opted to appeal to the Ontario Municipal Board to have it changed to the Bathurst alignment. It actually announced that it favoured a third route to the west, but if forced to choose, Bathurst was it. During the hearings, another proposal came onto the table from William Kilbourn to follow the Canadian National Railway. Nonetheless, construction on the transit line began in 1975 with the line opening from Bloor to Wilson in 1978 with two stations at Eglinton and St. Clair serving the Cedarvale area. The cancelled station at Heathdale explains long distance between stations.

Within Cedarvale Park, an emergency entrance at Markdale provides an obvious door into what lies below, but the rumblings of the subway are masked by the replenished canopy and wetland (albeit, the ravine like others in Toronto faces ecological collapse).

At Heath Street, one ascends out of Cedarvale Park near the north entrance of St. Clair West Station. Below, Castle Frank Brook continues under the subway station towards Nordheimer Ravine, leaving behind an area with layered history.

BlogTO – “A Brief History Of Castle Frank Brook, The Ravine Carver” by Chris Bateman

City of Toronto Archives – “A Work in Progress: Landscape Architects and Building Trades”

Discover The Don – “What Was Brewery Creek?”

Globe & Mail – “Got a Gate” by John Lorinc

Jay Young – “Searching For A Better Way: Subway Life And Metropolitan Grown In Toronto, 1942-1978”

Lost Rivers – “Cedarvale Ravine”

Spacing – “The fall of Sir Henry Pellatt, king of Casa Loma” by Chris Bateman

Till Next We Trod The Boards – “Toronto’s Heritage Apartments”

Toronto Dreams Project – “Casa Loma & The Crooked Knight”

Toronto Star – “Ghosts of Spadina Expressway Haunt Us Still” by Shawn Micallef

Transit Toronto – “The Spadina Subway” by James Bow

Urban Toronto – “A Pictorial History Of Toronto’s Cedarvale Neighbourhood” by Edward Skira

Wayne Reeves and Christina Palassio – HTO: Toronto’s Water from Lake Iroquois to Taddle Creek and Beyond

Discover more from Scenes From Toronto

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Wonderful research, Bob, I’m so grateful for all these primary sources — plus your photos of right-now and commentary to tie it all together. I’m going to forward this to my old Toronto walking partner, and suggest we explore this area the next time I am back in town!

Thanks Penny — Yes, I’d to read your findings! Hope the left coast is treating you well!

Yes, the left coast is treating me well … but I still love all that I knew in Toronto, and enjoy reading about the city in blogs like yours

Thanks, Bob; well done! (I live in Bracondale- visit sometime?)

Thanks Audrey!

Great piece of history. I didn’t realize that the Spadina line was as recent as the 1970s. When I arrived in Toronto in 1979, the line was already there.

I love ‘then and now’ photos, so the 50-year comparison of Bathurst St were my favourites. Hard to imagine the sprawl of Toronto today as mostly forest and fields 100 years ago.

The Cedarvale ravine has been on my list of parks to visit for some time. This post has just re-enforced that desire.